How Psychotherapy Works

Framing the Issues

History

Throughout history healers have used different methods to heal suffering, depending on their culture’s explanations of illness. In the study of cultures across the globe called Persuasion and Healing, Jerome Frank (1991) identified two crucial elements of this healing role: a socially sanctioned position in society; and knowledge of techniques believed to produce benefit in that society. In Frank’s study, the variety of techniques across cultures was enormous.

Sigmund Freud, in the early 20th century, brought a fresh method and set of ideas for understanding relationships between the surface manifestations of symptoms and the underlying meaning of these in personality and motivation. His method of analyzing, understanding and treating patients is called psychoanalysis. A psychodynamic (“talk therapy”) form of psychotherapy, it is the basis of much of the psychotherapy used today. Often these psychodynamic techniques are used by therapists with only partial or no awareness of the psychoanalytic origin of these techniques (Waldron & Helm, 2004).

In recent decades a wide variety of psychotherapies in addition to psychoanalysis have been developed. Common elements are shared by these “brands” of psychotherapy (Ablon & Jones, 1998; Ablon et al., 2006). At the same time, Freud’s psychodynamic therapeutic principles have been refined by decades of further development of clinical theories of therapy.

Why is there so much confusion of ideas in learning psychotherapy today? To understand this evolution, it is helpful to make a distinction between:

1. understanding how people’s minds and feelings work, which was greatly advanced by Freud’s discoveries;

2. the specific recommendations Freud originally made for psychoanalytic treatment.

Freud’s theories of the mind are still widely accepted today and are supported by neuroscience findings as well.

In the area of treatment, however, there have been great changes. Over the years, Freud’s methods evolved into a rather stilted technique. By the 1950s, a model of psychoanalytic treatment was taught which discouraged suggestion, giving advice, expressing a personal opinion or point of view, showing feeling or revealing anything about the therapist’s self, or even advising patients what they might do in life to feel better. Psychoanalytic treatment was supposed ideally to occur through interpretation alone.

There are perhaps two main reasons why American psychoanalysis developed these limiting recommendations: first, there was a wish among analysts to be as scientific as possible in their work, that is, to maintain a degree of objectivity that would do honor to the profession (Bettelheim, 1982). The therapeutic ideas of influential writers became enshrined, and human susceptibility to ideology took its toll. Second, there are indeed pitfalls for the young clinician in giving advice too freely. Patients with difficulties have ordinarily already heard too much of advice they are unable to follow. For both these reasons, suggestions in general became unacceptable.

These restrictions, however, were counter-intuitive, so many analysts often ignored them, and responded to the actual needs of their patients. And many other clinicians rebelled altogether against these strictures, leading to the sprouting of many schools of therapy espousing other ways to help patients change.

Furthermore, these restrictions were not based upon sound empirical explorations of what in fact helped different patients under different circumstances. It was only with the extensive study at the Menninger Clinic supported by the Ford Foundation, reported by Robert Wallerstein in his classic book of 1986 that the value of support was documented as having a powerful effect in some cases as the development of insight.

One painful example of excessive zeal in following narrow specifications for therapeutic treatment was described by John Bowlby, a well-known British psychoanalyst whose work led to the development of the field of attachment research. When he was in training, he presented a case to his supervising analyst, who was famous for clinical theories. Dr. Bowlby described an upsetting session with a young boy whose mother burst into the consulting room in an agitated state. His supervising analyst reprimanded him for addressing the child’s concern about his mother, saying he should just stick to the internal life of the child. Dr. Bowlby learned after the session that the mother had made a suicide attempt soon after leaving his office. He never returned to this supervisor. Two excellent studies (among others) reported better outcomes when therapists are more flexible [citations pending].

The field of psychotherapy remains with a largely inadequate empirical foundation to answer the classical question, paraphrased here: what treatment, for which patient, at what point in their unfolding relationship with the therapist, will prove to be most helpful? The latest extensive systematic effort to summarize what we do know is found in the two-volume 2019 edition of Psychotherapy Relationships that Work (Norcross & Lambert, 2019; Norcross & Wampold, 2019). But even this admirable study does not sufficiently address the issue of efficacy of long-term psychotherapy relationships, nor can it compensate for the dearth of careful long-term follow-ups to determine what psychotherapies with what patients conducted with what relational conditions, using what techniques actually lead to long-term benefit.

Follow-up studies have shown strong clinical evidence of changes after long term therapy and psychoanalysis (see Wallerstein, 1986; Sandell et al. 2000; Leuzinger-Bohleber et al. 2003,; Grande et al. 2012) but leaving three main issues requiring further study: how much might these patients have benefited from shorter or different treatments, or found their own way to a healthier life if treatment were not available? And the even more difficult issue remains insufficiently studied: how much variation in outcome is the result of the variation in therapist gifts to conduct therapy? Finally, the results support the value of long-term therapy, but not with the thoroughness that our field would benefit from, and without the careful exploration of treatment failures among the group of former patients over time.

The PRC research group explores which elements emphasized by psychodynamic theories demonstrably help patients over and above the benefit of the non-specific elements common to all therapies. The evidence we and others have developed (Waldron et al. 2018; Høglend et al. 2011 and many others) support their importance.

Beginning of Treatment

Three phases have been described as typical of a psychotherapeutic encounter (Howard et al., 1993;)

- Improvement of subjective well-being (occurring within a session to a few sessions).

- Reduction in symptomatology (requiring a few to many weeks).

- Enhancement of life functioning and character or personality change (requiring a longer time).

The first phase tends to occur due to the power of nonspecific factors (“common elements”) in the psychotherapeutic situation. When a suffering individual seeks psychotherapeutic help, there is usually an immediate benefit which has been described as the restoration of hope or of morale, activated in most people simply from seeking help.

Hence the finding of similar early results in studies of different “brands” (Ablon et al., 2006) of short term treatment at or soon after the completion of treatment. However, for long standing and complex personality problems, these short term benefits tend to disappear with time, unless changes are accomplished in the underlying personality issues which contributed to the development of a clinical illness (Shea et al., 1992).

A psychodynamic psychotherapist attempts from the outset to engage in a conversation about the patient’s presenting difficulties, while simultaneously learning about the patient as a person: personality traits, patterns in how the patient relates to others, strengths as well as problems, and how the patient sees him/herself. A clinical diagnosis based on symptoms is not nearly as useful as the formulation of a flexible and workable description of the patient as a whole because formal diagnosis itself tells so little of the nature of the person (Lingiardi and McWilliams, 2017, McWilliams, 2011).

Patients respond to an initial offer: “How can I help you?” This direct approach gets right to the point of the therapeutic encounter. An open-ended question like this can allow the patient directly to address what is top of mind.

Developing a Relationship

How therapist and patient relate to one another is of central importance. The therapeutic alliance is the widely used term in recent decades, because, as measured, it correlates often with therapeutic benefit. “Therapeutic alliance” may be described as simply the relationship (see Norcross’ edited book, 2011, Psychotherapy Relationships that Work.)

The relationship is not just a matter of being friendly. There are occasions when confronting the patient in a challenging way may mark a positive turning point in a treatment, even though an excessively confrontational approach to patients has been shown to have negative results (Norcross 2011, p. 427).

Building the relationship can also be helped by awareness of cultural differences (Lingiardi et al., 2017; Werbart et al. 2018).

Feelings the therapist has while listening can give important clues to the patient’s experiences and concerns, sometimes not available to the therapist consciously. Also, through the highly-individualized process of immersion in a patient’s emotional experience and inquiring more about it, the therapist has the opportunity to foster curiosity and further reflection in the patient. In favorable cases, a patient responds with greater trust in the therapist’s understanding, empathic connection, challenges, and confrontations.

Therapists tend to fluctuate between sharing in the patient’s emotional experiences and separating themselves enough from these experiences to examine them in a different light, a potentially tactful oscillation between empathic resonance on the one hand, and expressing different vantage points that can stimulate novel reflections.

Listening attentively is experienced by most patients as comforting, especially with careful attention to the patient’s feelings, including those they may not have been aware of. The therapist is there for the patient, listening and witnessing aspects of the patient’s emotional life that may rarely be disclosed to anyone else.

This availability often evokes strong feelings in the patient. Leo Stone wrote a slim book that describes some of the early origins of the feelings evoked, called The Psychoanalytic Situation (1977).

A relatively unexplored aspect of building a relationship is humor. Such an important ingredient in most friendships, humor by the therapist can be misused to distance from, minimize upsetting feelings, or diminish the patient. On the other hand, it is possible to draw attention to aspects of life in a light way that can aid in opening up important topics for discussion. Often the patient feels less ashamed and more accepted. There are several examples in the four sessions of our patient “Annie” in which just such a light and humorous touch appears beneficial.

Next steps

If you have not done so already, we recommend taking the time now to familiarize yourself with this therapeutic pair by listening to and/or reading the first four sessions of the case of Annie. You will have a chance to see what the sessions were like, and your experience should enrich your study of the categories describing psychotherapy that we offer below.

Or if you prefer, read on to acquaint yourself with our categories before studying the clinical material. We have found value in studying the case material more than once.

The classifications of Annie’s therapist’s turns of speech (TOS) are given at the end of each rated TOS, and are linked to the categories described below. So you can navigate back and forth at will. And you will be able to click on the comments on what is going on provided by experienced clinicians. To go to the case of Annie, here is the link.

Dynamic and Relational Components of Therapeutic Work

Dynamic Categories

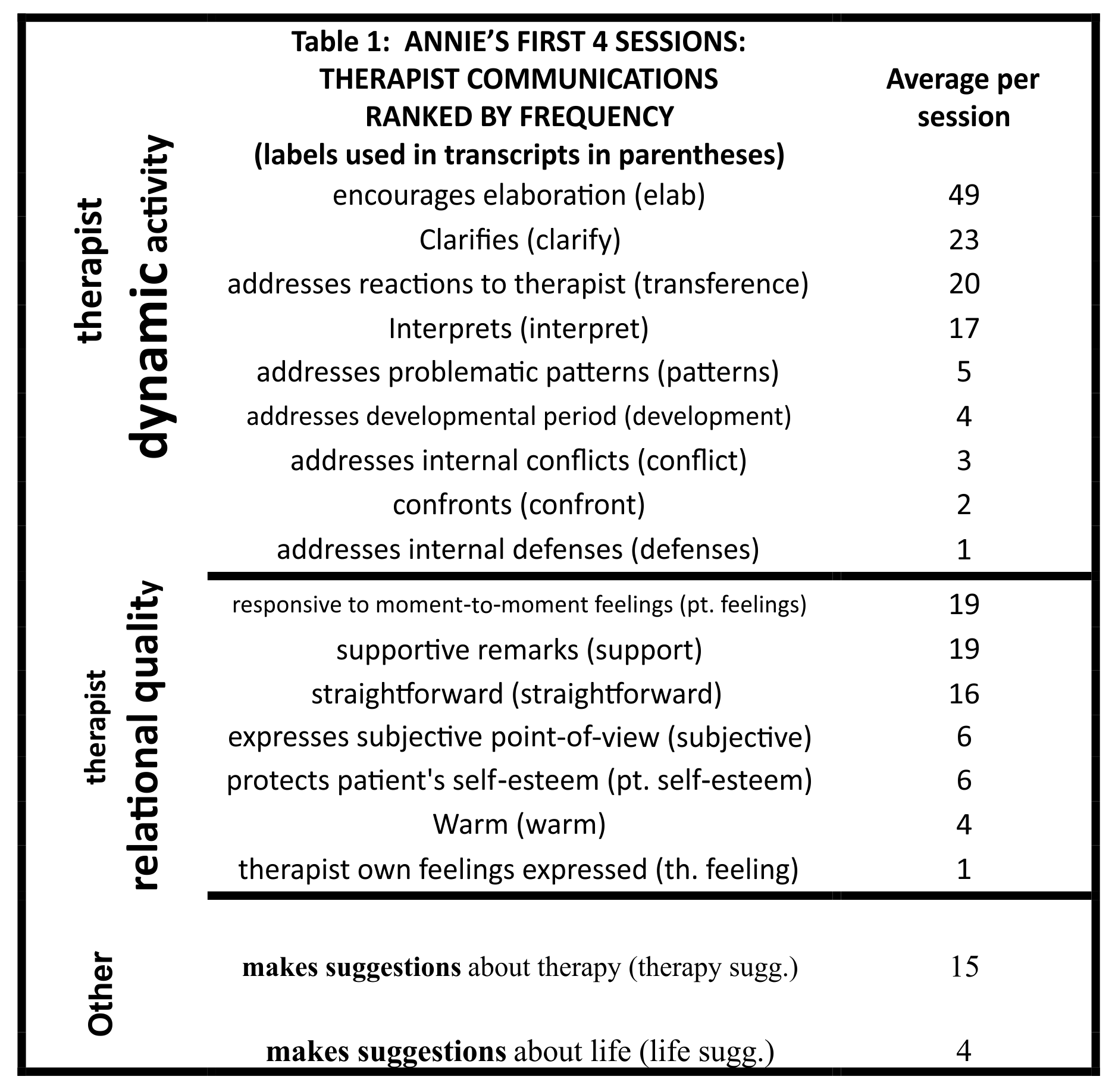

We introduce each of the categories of therapy immediately below, organized in the same order as Table 1. In each category below, there is a link to our psychotherapy manual to further definitions and examples at different levels of intensity for that category.

Encouraging Elaboration

Encouraging elaboration comprises much of the therapist’s contribution to the conversation in the beginning and throughout therapy. It is a straightforward means to add to one’s knowledge of the patient’s thoughts and feelings, and, if done tactfully, can provide a safe, unobtrusive environment for the patient to explore new emotional territory or further reflect on him/herself and others.

It is useful to encourage elaboration based upon what the therapist discerns, particularly when the patient seems to pause or veer away from a deeper elaboration of a topic (Paniagua, 1991). Particularly, the therapist does well to pursue tactfully any traces of feeling the patient may reveal.

Closely related to encouraging elaboration is allowing silences to occur in the conversation, when the therapist has the impression that the patient may very well continue. It is interesting how often patients will only have a dream come to mind in just such a period when the patient is struggling in her communicating. There is an example from such hesitancy in one of Annie’s sessions, her therapist waiting, then the emergence of a dream, In session 4, paragraphs 40 to 52.

In the first few meetings, patient and psychotherapist typically discuss how or why the patient’s emotional life has led to a consultation at this particular time. Ideally, patient and psychotherapist become collaborators in describing the nature of the patient’s problems. Moreover, in the elaboration of this conversation, patient and psychotherapist can revise or clarify any disagreements in how they each view these difficulties.

Encouraging elaboration is the first tool described with a case illustration in our PRC Psychotherapy Manual, the case of the angry man (click here).

Clarification

Patients generally know what their upsetting feelings are when they come for help, but usually they don’t understand the full connections or implications of their feelings. Feelings of shame and guilt are painful, and people want to avoid experiencing such feelings, so they may have difficulty keeping many aspects of their situation in mind. The therapist’s effort to clarify elements contributing to their unhappiness may often be the patient’s first experience of the therapist’s ability to understand them. This can often also help the patient develop curiosity and trust that the therapist understands them adequately enough that he/she may have something meaningful to add. Click here for the case of the sexually anxious young man, with a further definition of clarification.

Addressing Reactions to Therapist or Therapy (addressing transference)

Annie’s analyst was very much influenced by James Strachey (1934) and Merton Gill (1982), whose writings anticipated the neuroscientific findings indicating that it is experience, not insight itself, which causes alteration in patterns of feelings and coping (Vaughan, 1998). Subsequently, the way experiences in therapy tend to lead to beneficial change has been explored from a neuroscientific point of view (Lane and Garfield 2005). An exceptional controlled study by Høglend and colleagues (2011) demonstrated that addressing the feelings of the patient toward the analyst or analytic situation led to important changes. Annie’s analyst reflects this view in his technique, with his quick approach to her feelings which make her uncomfortable about working with him.

It is our view that there has been an excess of emphasizing only one method of change in psychotherapy. We believe it makes more sense to explore at least two modalities leading to beneficial therapeutic change: experiences within the therapeutic pair and experiences in life outside the pair which are altered as a consequence of therapeutic impact or influence. For example, after therapeutic work on a patient’s negative expectations from a boss, the patient alters approach to the boss and a virtuous cycle can occur, which can cement the patient’s altered expectations. This realm has particularly been developed by a variety of cognitive behavioral therapies, and by family and couple therapists.

The PRC Psychotherapy Manual illustration of a man who missed his therapist as an example of addressing transference may be reached by clicking here.

Interpretation

Clarification and interpretation differ in the degree to which the patient appears to be already aware of what the therapist points out. Interpretation implies the therapist is offering an understanding that is not previously within the patient’s awareness, whereas a clarification may make connections of elements the patient has already described. The distinction is a matter of degree. Both clarification and interpretation can contribute to the patient’s sense of being understood and helped, provided sufficiently tactfully presented.

Interestingly, one immediate response by the patient to an interpretation that has proved to be an indicator that the interpretation is, in fact, correct is the response, “I never thought of that.” In favorable circumstances, this leads to increasing curiosity and expanding opportunities for exploration and reflection.

The single most under-emphasized aspect of understanding a patient is the importance of understanding the patient’s feelings, including those that the patient may not be aware of (Greenberg 2016). Inquiring about or acknowledging the patient’s feelings will often open up the conversation in directions the patient may find relieving. If in doubt about the patient’s feelings, better to express an inquiry or offer a tentative thought, rather than being definitive. In fact, a more respectful style is to be preferred anyway. A tentative interpretation (even in the form of a question) of a feeling about which the patient is unaware can develop trust that the therapist is flexible enough to understand aspects of the patient that they had not fully appreciated, and can provide a stimulus for patients to think more about their feelings generally.

Descriptively, one can note whether the focus of an interpretation concerns the patient’s current life outside of the therapy, the patient’s past, or reactions within the therapy situation. No general principle can be claimed for the choice, although there are fine studies dating back decades showing that linking those three situations often is therapeutically effective, the so-called therapeutic triangle (Malan, 1976).

Freud, who greatly valued ideas and intellectual understanding, was naturally inclined to the belief that the patient understanding such hidden connections (developing insight) would lead directly to therapeutic benefit. Seeking explanations, i.e. developing insight, was Freud’s own major method of mastery, when it came to feelings that seem alien or out-of-control.

But insight does not represent the full panoply of powerful interpersonal factors activated when an individual seeks the help of a healer. This is reflected in the title of John Norcross’ excellent edited book: Psychotherapy Relationships that Work (2011). The relationship between patient and healer appears to be the vehicle for change, which is then facilitated by repeatedly bringing to awareness the troubling feelings which the patient has wanted to keep out of awareness (Lane and Garfield, 2005)

On the other hand, there is little doubt that, in a well-functioning individual, insight about one’s own patterns of behavior and what drives them often leads to changed behavior, which in turn leads to changed patterns of experience that become self-perpetuating. More recent research has begun to examine the balance between various components of the therapeutic process that contribute to emotional benefit, but much more data is needed than is currently available (Waldron et al. 2018),

Click here for the case of the woman who lost her brother, along with further description and illustrations of interpretations.

Addressing Problematic Patterns

How well is the therapist working with and helping the patient work with typical patterns of relating and patterns of feelings which most trouble his/her life adjustment or satisfaction?

Carrying forward tactfully this aspect of therapeutic work is central to developing and maintaining the therapeutic alliance, because the patient experiences directly the potential benefit. Recognizing patterns is one first step to altering them. Patients come to treatment often suffering painful feelings – anxiety and depression are most common – and don’t realize initially how these feelings almost invariably stem from characteristic problems they have in living – problems of character (McWilliams 2011). Success in tying such patterns to more than one aspect of a patient’s life, past, present, and with the therapist enhances effectiveness (Malan, 1976).

Addressing the Developmental Period

Psychoanalysts are often criticized for being preoccupied with the patient’s past, and thereby neglecting the present. This oversimplification is probably true in certain instances. On the other hand, many patients feel relief when their symptoms or painful feelings fall into a meaningful pattern, and they can see that, however maladaptive their symptoms or behavior may be, it is possible to be less condemning and more understanding of themselves.

The therapist’s success in helping patients realize the self-defeating nature of their past and present behavior is also crucial to engaging them in the painful process of self-recognition and change in self-management or behavior with others, to create a better future.

But the one – recognition of the influence of the past on the present – does not preclude the other – recognizing the impact of one’s own behavior on one’s future.

The case example of the promiscuous woman in our PRC coding manual illustrates this approach. Also, in the case of Annie, the therapist carefully delineates the antecedents of her dread of being seen as: bad, wrong, or deserving of criticism in several instances in sessions 2 and 4.

Addressing Internal Conflicts

Brenner (1982) helped to clarify the relationships among wishes, fears, impulses, feelings, and defenses against them. There is conflict in the mind among various elements. Much of behavior and particularly symptoms and character structure may be best understood as result of compromise formations in attempts to deal with conflicting feelings. This can be true of anything, from the primitive defense of projection, in which evil motives are attributed to others, to the mature defense of altruism, perhaps arising from unfulfilled longings to be taken care of oneself.

The role of internal conflicts is evaluated in a German instrument called the Operationalized Psychodynamic Diagnosis or OPD. Many years of work eventuated in an elaborate system for assessing personality, which takes extensive training to become competent in using, reflecting the inherently complex nature of personality functioning. The role of conflict plays an important part in OPD assessment (Lingiardi and McWilliams, 2018, pages 901-903).

The case of the embarrassed woman provides a more extended description and example of addressing conflict from our PRC coding manual.

Confronting the Patient

In one way or another, the patient will bring problems into the consulting room. The therapist may not realize this is happening, or not know what to do about it. A much beloved teacher at the New York Psychoanalytic Institute, a very courteous and mild-mannered man named Leo Stone whose writing were cited in the section on developing a relationship, had a patient in psychoanalysis for a long time. She always demanded some special scheduling consideration, but was never satisfied with what was offered. Finally, at the end of one session, when she expressed dissatisfaction, he threw his pen down on the desk in exasperation and said, “What DO you want anyway?” He described this moment as the turning point in her treatment.

The implication is not that the therapist should follow his/her impulses by getting angry at the patient. Rather, one needs to be aware that important issues may be avoided, consciously or unconsciously, by the patient and even the therapeutic pair. Recognizing this and taking appropriate action may move a stalled treatment off dead center.

The therapist needs to respect the prompting of his/her own mind, particularly of parts of the mind one is not fully aware of. An interesting example of the way the therapist’s unconscious mind may contribute to the treatment may be found in Waldron’s study of “Slips of the Analyst” (1992). Here evidence is presented suggesting that therapists have parts of their unconscious mind directed to the task at hand (helping the patient). Attuning oneself to those messages can be beneficial.

The case of the impulsive egg donor illustrates confrontation.

Addressing Defenses

There is a wide variety of defenses, as may be seen in our PRC manual introduction to defenses. Defenses overlap with coping strategies, since they are methods of dealing with unwelcome feelings, thoughts, perceptions, or impulses.

Many years ago, Chris Perry began to study the relationship between defenses and overall psychological health. He worked with George Vaillant, who studied coping and life trajectories (Vaillant 2012) and participated in the long-term follow-up study of Harvard students (which incidentally included John F. Kennedy). Perry developed a classification of defenses, rating them on a seven-point scale as to what level of psychological health each represented. This classification was based on the writings of Erik Erikson (1963) in which he outlines the famous eight ages of man.

Perry does not focus on coping strategies as such in his evaluations, but instead on the notion of mature and immature defenses (Perry and Høglend, 1998; Roy et al. 2009). His method of systematically assessing defenses provides a useful way of evaluating the impact of treatment. Perry’s scoring of defenses as more or less adaptive is an interesting way to tap into the changes that occur in successful treatments.

In considering defenses as a major way to understand disturbed functioning, one needs to keep in mind that defenses, or coping strategies, will vary in how adaptive or maladaptive they may be under varying circumstances. The goal of treating an individual with a severe handwashing compulsion, unable to leave his home, is not to cause a cessation of handwashing. In a lively discussion of a patient whose defenses were contributing to a lack of satisfaction in life, Charles Brenner (1976) comments that defenses do not disappear with treatment, like a lap when one stands up. An extended case example (pages 65 to 78) shows that it is the balance in a person’s life, the degree of comfortable and gratifying functioning, by which one may judge the appropriateness of the defenses/coping strategies.

Anna Freud (1936) provided an encompassing description of defenses still useful today. The central point is that virtually any aspect of human functioning can serve maladaptive, overly defensive functions, interfering with quality of life.

In the PRC manual, the case of the teacher with an ulcer illustrates addressing defenses.

Relational Categories

In describing relational aspects, our manual does not provide examples, because it would require far more material to capture the tone or presumed impact on the patient than for the dynamic variables. However, you may wish to check out our Manual description of any of these categories by clicking here.

Responding To Moment-To-Moment Feelings

The therapist needs to be closely attuned to the conscious and unconscious feelings of the patient. Jonathan Haidt, in his splendid book The Righteous Mind: Why Good People Are Divided by Politics and Religion makes the analogy that the conscious mind is like a rider on top of an elephant, maintaining the comforting notion of steering the animal. In reality, the rider learns to agree with the direction the elephant, the unconscious mind. chooses to go.

The therapist will arrive at a deeper rapport and understanding of the patient by paying close attention not only to the feelings of the patient, but also to his/her own feelings in reaction to the patient, even if it is not obvious what has prompted them.

In the first four sessions of Annie, there are many occasions when the therapist pays careful attention to hints of the patient’s feelings, and frequently his inquiries based upon his awareness led to a productive engagement.

Supporting the Patient

Patients who come to see therapists are suffering. Most also feel a sense of failure at being unable successfully to deal with their problems. Accompanying feelings can include anxiety, guilt, grief, and shame. Consequently, the first priority may not be clarifying or interpreting, but rather supportive remarks to ease the patient’s distress. Relief from distress can empower the patient to be more curious and think further about him/herself. Supportive statements can include straightforward guidance, statements of reassurance, or explicit acknowledgment and validation of the patient’s perspective.

There is often a supportive element intertwined with interpretations, clarifications, and confrontations. Being open to one’s own feelings in response to the patient can lead to more timely and appropriate comments.

Much of the art of psychotherapy is in the therapist’s awareness of how to support positive feelings and avoid stimulating overly strong negative feelings in the remarks they make to their patients. This capacity for empathy was particularly prominent in the way Annie’s therapist anticipated how she might feel, and found ways to phrase things to acknowledge her contributions and her strengths while discussing other features of her functioning that might make her feel uneasy or ashamed. Here is an illustrative excerpt from her second session. Of course, the supportive tone can only be heard in the audio.

69 P: Well, I know I’m overtired and, you know–and I’ll probably say a lot of things that–you know when you’re overtired you probably say things you mean but you don’t mean, you know. you usually don’t say them. you can, uh,

70 T: You know that’s a very important point. You’re not gonna be held to anything you say. you can change your mind, that’s-

71 P: Really?

72 T: Yes. That’s the whole idea.

73 P: If I say one word you won’t take it in one direction and that’s the way she must really feel?

74 T: No. I won’t. I understand that this is a situation in which you’re gonna speak freely and you can’t say everything at once. you may express certain feelings about something and you may have exactly opposite feelings about the same thing that you express on another occasion.

75 P: I can see the words sometimes but I can’t express what you’re really feeling.

76 T: That’s right. Don’t feel you’re going to be held strictly to account for everything you say.

77 P: Okay. That-that was going through my mind.

78 T: That goes for me too. I may make this, that or the other suggestion just because it seems to me to be a possibility–not because I’m laying down the law.

The therapist’s comments in this sample were also classified in other categories (addressing moment-to-moment feelings and suggestions for therapy, as described below). Such overlapping classifications are quite typical of therapy work.

An important aspect of support is the acknowledgment of patient’s progress, which strengthens the therapeutic alliance particularly for patients who have experienced their parents as not being aware of them very fully. More generally, if you are aware that there are aspects of the patient’s relationships with important parental figures, a failure to differentiate yourself in the patient’s mind from their parents may stall a treatment in ways that may not be obvious.

The case of the impotent man illustrates different levels of support.

Straightforward

Patients need to develop trust in their therapist, and will also do better if they are able to feel they know the therapist as a person, and respect him/her.

This does not imply that the more personal information therapists share, the better, or that they can express a viewpoint for their own pleasure or satisfaction. But the cardinal importance of allowing the relationship to build in a positive way means that evasiveness will serve the treatment poorly.

Some beginning therapists are afraid of the patient asking intrusive questions. Being straightforward can help in such an instance. If a question is experienced by the therapist as being inappropriate, that feeling can be shared as part of an inquiry. For example, is the patient unaware that the therapist might feel his/her personal space intruded upon by these questions so early in the treatment?

Expressing Subjective Point of View

In ordinary conversation, people count on turns of speech to have a sense of shared participation. Of course, psychotherapy interviews are not ordinary conversation (see below the section about “Making Suggestions about Therapy”).

In decades past, the emphasis was on remaining neutral and abstinent, to make the contact between patient and therapist like a sterile operating field, not contaminated by the contribution of the therapist. But this distorts the human experience of coming for help to a hopefully trustworthy figure.

Inevitably the therapist’s personality is going to be perceived by the patient, unless the patient is so severely Asperger in relation to others that he/she is oblivious. Expressing a point of view may well be seen as helpful and responsive to the patient’s needs. In this respect it shows an appropriate interest in the patient, both in terms of problems and of strengths, and can increase a patient’s comfort level and make progress that much more likely.

The more experienced therapist attempts to be always attuned to responses to the patient, and considers them a continual data feed about the patient in ways that cannot be fully articulated. As in most aspects of life, moderation is to be desired. But many experienced therapists feel comfortable in being more open and spontaneous, while keeping the patient and the possible impact of what they say in mind.

In all the sessions with Annie, her therapist is quite straightforward and expressive of his point of view.

Protecting Patient’s Self Esteem

When patients come for treatment, they are usually in a vulnerable state. In order to make them sufficiently comfortable to be open about problems they face, it is often necessary to reassure them.

In Annie’s case, there are a number of times when the therapist acknowledges the patient’s positive contribution, or is gentle in tone in the way he confronts her, with a light touch and a sense of humor. These are listed in the ratings of the analyst’s turns of speech accessible in the excel file listing our ratings of therapist’s turns of speech.

The case of the self-critical businessman illustrates the therapist dealing with self-esteem problems.

Warm

This characteristic could equally be called responsive to the patient’s emotional state. It implies the opposite of standoffish, cold, unresponsive. These qualities do not ordinarily help to build relationships.

Therapist’s Own Feelings Expressed

This overlaps with expressing subjective point of view, being warm, and straightforward.

In the four sessions with Annie, the therapist did not express his own feelings very much, but was emotionally there. There is an example of such feelings in the PRC coding manual case of the woman with money problems, accessible here.

Other

Making Suggestions About Therapy

Psychotherapy is indeed a special kind of conversation, so there are about a dozen such remarks on average through the four introductory sessions of Annie. Patients expect to be told how to behave by the expert they consult with. The primary efforts are to learn more about the patient and his/her feelings. In a way, the therapist is teaching the patient to pay attention to the various products of his/her mind, whether it be feelings, thoughts, memories and so on, and to share them with the therapist, without pre-judging whether they are valuable or not.

In a sense, the therapist is recommending to the patient to “trust the force”.

Making Suggestions About Life Outside Therapy

This area is the one which needs the most careful consideration and investigation. In order to explore it, we begin with a story from a retired senior colleague, widely respected, and thoughtful about his relationships with patients and others.

A married man with young children came in to see him, and soon it turned out that this affable, successful man was unaccountably abusive toward his children. Rather early in his treatment, he recounted this pattern, and then asked, “Dr. J., I think it is going to take a long time for us to figure this out.” Dr. J. replied, “Why don’t you cut that shit out right now?”

The treatment went well and was terminated. Several years later the man died, and the analyst, living in a relatively small community and being that kind of person, went to the funeral. To his surprise, several of the family members came up to him and said, in effect, that he had had an enormous positive impact on the family, for which they had remained grateful all these years.

Dr. J. had an intuitive understanding that this man needed to be talked to in this way. There developed evidence later in the treatment that his patient’s father had been abusive, so Dr. J., in making this suggestion in the way he did, set an example of an altogether different sort of father figure, which his patient needed to hear and experience.

All of this took place at the level of intuition. He did not have the information at the time to be able to figure out consciously what advice this patient needed, nor was it the kind of approach that, as a psychoanalyst, he normally took. Yet, his intuition guided him and he trusted it, to the benefit of the patient.

One last story illustrating the same point, from a reliable source. A psychiatrist had been treating a very sick patient for some years. One time she came in for her session, and everything seemed unchanged. But after she left, the psychiatrist felt compelled to call her husband and said “you’d better go home right now.” It turned out that the woman was planning that day to kill her children and herself.

In conclusion, modesty and careful exploration are called for, with careful follow-up studies, to find out what elements in psychotherapy turn out to have been helpful in the years after.

Efficacy of psychotherapy

There have been a number of studies of long-term psychotherapy and psychoanalyses which have confirmed these benefits via clinical illustrations (Wallerstein 1986, Schachter, 2005, Fischer, 2011, Breger, 2012). In addition, there are countless case studies of individuals, of which we cite one by Josephs and colleagues (2004) because the methodology as well as the conclusions stand out. The authors, using several independent research methods applied to recorded sessions, are able to demonstrate the valuable results of slow and painful work over time with a substantially character-disordered patient.

A central organizing principle may be emphasized here: the varieties of human character, traumatic experiences and consequent ways of coping mandate therapist flexibility, responsiveness, and patience over time, combined with devotion to the patient.

Three different manualized therapies have these organizing principles in common. All are based on working with feelings arising in the relationship with the therapist. They are Transference Focused Psychotherapy developed by a large research group led by Otto Kernberg; Mentalization Based Therapy developed by Peter Fonagy and many others in the UK; and Milrod and colleagues’ Panic Focused Psychotherapy. The therapies are described extensively in “The significance of three evidence-based psychoanalytic psychotherapies on psychoanalytic research, psychoanalytic theory, and practice” by Elizabeth Graf and Diana Diamond (chapter 6 in Axelrod et al. 2018).

These groups have demonstrated that core psychoanalytic principles enhanced short-term and medium-term treatments in comparison to other therapies. All share the goal of helping patients to manage and accept their feelings in a less destructive and more integrated way and at the same time, to become more aware of the feelings and states of mind of others.

These benefits occur even with severe limitations on the length of treatment. Psychodynamic clinicians know from experience how many years of treatment are often required to help individuals overcome chronic difficulties. Documenting this more extensively is still a task for the future.

The nature of benefit from psychotherapy is also often different from what led patients to treatment in the first place. At the beginning of treatment most patients are eager to address troubling symptoms, such as anxiety, depression, and a wide variety of other symptoms. In the course of therapy, as patients become more aware of their own contributions to their unhappiness, their goals typically change, often as a direct result of the therapy.

A careful study published nearly twenty-five years ago explored how the benefits of even relatively short-term psychotherapy clustered under four main categories (Connolly and Strupp 1996):

- improved symptoms

- improved self-confidence

- improved self-understanding (later modified to self-understanding of interpersonal patterns (Connolly et al. 1999)

- greater self-definition.

A fifth category added later, improved compensatory skills, or coping skills, refers to interpersonal and self-management competencies developed under the stimulus of therapeutic work (Connolly et al. 2009). Therapist remarks enhancing coping skills are included among our “components of therapy” in the “suggestions for life” category. They have been explored extensively by practitioners of cognitive behavioral therapies.

Items 1 and 2 are benefits patients expect in successful therapies, whereas the others are ones they may not have been searching for at the outset, but come to value later.

Parts in Preparation

(with illustrative cases)

Uses of the dream in psychotherapy

Working through conflicts and problems in longer term therapies.

Working with multiple members of the same family.

Further Development of Our Classification System

For this website, we wanted to include activities not part of the typical psychodynamic toolbox as well, so we studied three instruments which were specifically developed to tap the full range of therapist actions in psychotherapy (Jones & Pulos, 1993; Hilsenroth et al. 2005; McCarthy & Barber 2009). McCarthy and Barber’s “MULTI” scale, being the most recent and comprehensive, serves as a good introduction to the variety of psychotherapeutic interventions. We have altered their classifications of 60 types of therapist comments because, in our view, many of the items listed belong in the category of psychodynamic technique as actually practiced by many contemporary psychodynamic practitioners. Many of these can also be described as “common factors,” relevant to most types of psychotherapy.

We re-classified 42 of the 60 types of comments as within the psychodynamic umbrella. We divided the remaining 18 types of interventions into three categories: 6 are suggestions in regard to therapy (“suggestions for therapy”), and 12 are suggestions to patients for what they might do to improve their life outside the therapy room (’suggestions for life”). There are also two suggestions that apply both to therapy and to life outside the consulting room, and finally two which don’t fit into our classification system. To inspect our modifications in Excel of the McCarthy and Barber’s MULTI Click here.

In their list, there is an interesting mix of suggestions, which is no doubt added to each time a clinician invents or discovers a new type of suggestion, and then sometimes immediately adds to the literally thousands of newly named therapies, so that the clinician new to psychotherapy feels quite overwhelmed, and the experienced clinician throws up his/her hands!

However, we believe that most therapists would benefit from a careful consideration of the nature and results of a variety of therapist suggestions. There is no doubt that the field needs much more extensive examination of what works for whom under what circumstances, and what benefits may accrue from creative approaches across the wide range of patients seeking therapeutic help. The role of suggestions of various kinds appears to be an important dimension for further study.

CORRELATIONS AMONG THE THERAPIST VARIABLES:

The dynamic activity variables are quite independent of each other. Correlations greater than .5 were few, and are listed here. To find out how much variance is shared based upon a correlation, square the correlation. Pearson correlations can vary from -1.00 to +1.00. A Pearson correlation of .5 means the two variables share only one quarter of the variance.

Therapist interprets correlates with addresses problematic patterns .55, also with therapist addresses defenses at .55, and with therapist addresses internal conflict at .66. Therapist addresses problematic patterns correlates also with therapist addresses internal conflicts at .62. Therapist addresses defenses correlates with addresses conflicts .67.

In contrast to therapist dynamic activity, the seven variables constituting therapist relational quality correlated strongly with each other, from a low of .45 for therapist supportive with addressing moment-to-moment feeling, to a high of .82 for therapist straightforward with therapist warm. Even a correlation of .82 shows a shared variance of only 64%, so we believe it worthwhile to keep all seven variables.

For access to the Therapists Turns of Speech (TOS) scores, click here.