Advancing Psychoanalysis and Psychotherapy

through Research

Sherwood Waldron, Francesco Gazzillo, Karl Stukenberg and Bernard Gorman

November 19, 2017

The need for research

Research related to psychoanalysis has been fruitful in many areas. For instance, research on psychological development and attachment (e.g. Eagle, 2011, Fonagy, 2001, Stern, 1985) and on the neuroscientific bases of psychological functioning (e.g. Schore, 1994; Solms, 2017), has greatly enriched the empirical basis of psychoanalytic ideas. It has led to support for many important psychoanalytic theoretical propositions and modification of others.

This discussion will focus on two related areas where additional research could have enormous impact: the processes and outcomes of recorded psychoanalyses. Such studies have been much rarer than is warranted. More extensive direct study of recorded psychoanalyses could lead to substantial refinements in techniques that benefit patients, more support for the value of psychoanalytic treatments, and enrichment of psychoanalytic education.

Freud believed that being steeped in the psychoanalytic method was the only means of appreciating the impact that the unconscious had on the functioning of the individual, and was quite skeptical about the possibility that carefully devised empirical studies could test psychoanalytic hypotheses more convincingly than direct clinical experience (Schachter & Kächele, 2012). That said, Freud was a strongly empirical investigator. Originally trained as a rigorous empirical physiologist, he collected over a thousand dreams in developing his breakthrough Interpretation of Dreams (1900) and was quite humble about the conclusions he drew in Mourning and Melancholia (1917) because of the limited number of cases upon which he based his theories.

In order to advance psychoanalysis as a therapy, it is necessary to study both the outcomes of psychoanalyses, in comparison with other therapies, and the relationship between differing processes and subsequent outcomes with differing patients. Open questions about psychoanalytically informed practice mirror questions that have long been raised about psychotherapy generally (e.g. Beutler and Clarkin, 1990). These include determining any differential benefit patients receive from therapeutic work using psychodynamic techniques compared to other approaches such as cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) that normally require less time and expense (Gabbard and Westen 2003; Huber 2017); determining which patients benefit from which therapeutic techniques; and determining the role of the therapeutic relationship as a mediator of therapeutic techniques leading to benefit (Beutler and Clarkin, 1990; Gabbard and Westen, 2003; Norcross, 2011). It would also be desirable to determine benefits accruing from increasing experience, and from differing quality of supervision of cases.

A major obstacle in the last decades has been the reluctance to make audio recordings of psychoanalyses for research purposes. Medicine would never have advanced without direct study of the human body, even though such study was forbidden for a long time. The direct study of psychoanalyses via recordings has only been carried out by a relatively small number of pioneers, because of the anxiety of the great majority of psychoanalysts to record their own work. The work of the pioneers has demonstrated that psychoanalyses conducted with recordings resemble those done without recordings, at least as far as the psychoanalyst clinicians collecting them and those studying them are concerned. Yet the reluctance to expose one’s own psychoanalytic work has impeded scientific progress, and the standing of psychoanalysis as a treatment.

Our group has used recordings of psychoanalyses, a technology scarcely available in Freud’s time, and careful rating of the process of the analysis to arrive at reliable means of generating psychoanalytically valid data that can be statistically analyzed using modern techniques (Waldron, Gazzillo, & Stukenberg, 2015; Gazzillo, et al., 2017). This window into psychoanalytic processes itself can, we believe, help substantiate core psychoanalytic theories about how the technical processes of psychoanalysis work and can help bridge the gap between clinicians and researchers as the understandings developed by researchers are enriched by clinical understandings. This is a critical need for the future as we face increasing demands from consumers, third party payers, and clinicians in training for therapies guided by evidence (Westen, Novotny, & Thompson-Brenner, 2004). While psychoanalysis will never become a purely data-driven technical discipline, it is critically important that we be able to speak the lingua franca of modern scientifically based care. This chapter will illustrate what has been accomplished so far as well as tracing the needs and goals for expanded studies of the processes and outcomes of recorded psychoanalyses.

What distinguishes psychoanalysis and psychoanalytic therapy from other treatments?

When we speak about psychodynamic or psychoanalytic techniques, there are certain core aspects which are widely shared among psychoanalysts: the importance of understanding patients’ troubling feelings and patterns of cognition, emotion, motivation and relationship, and their internal conflicts that underlie and sustain these troubling patterns. We develop this understanding by observing the patient’s reactions within the therapeutic setting, and understanding as best we can the psychological world the patient inhabits. This is usually facilitated by attending not only to what the patient says, but attending to our own feelings occurring as we talk with them (Gazzillo et al., 2015). Therapeutic communication is intended to deepen the patient’s own awareness of these same aspects, leading to beneficial changes in their lives (Gullestad, et al. 2013). We will outline below some of the evidence that these aspects of psychoanalytic work benefit the patient.

There are nevertheless common results among different varieties of treatment, something that was referred to by Rosenzweig (1936) as the “Dodo Bird” effect (Luborsky, Singer & Luborsky, 1975). There have also been efforts to understand common mechanisms that may underlie this effect (e.g. Gerber, 2012; Wampold & Imel, 2015). Many researchers have also found that there are common techniques used by differently named psychotherapies (e.g. Ablon & Jones, 1998; Sloane et al., 1975; Waldron & Helm, 2004). However, the apparent relative equivalency of all therapies in short-term effect on symptoms does not address the impact on subsequent life. This is particularly true for patients with severe or complex disorders, which are usually related to personality organizations that predispose to a variety of psychological malfunctions, and which are correspondingly unlikely to respond very fully to brief therapy, even if the immediate symptom (depression, anxiety, etc.) is alleviated for the moment (Huber, 2017; Westen, Novotny, & Thompson-Brenner, 2004).

Within what might be called the psychoanalytic umbrella, there also is a profusion of techniques, probably not differing from each other as much as each theoretician believes. A group of colleagues wrote a paper whose title captures the problem: “Beyond Brand Names of Psychotherapies” (Ablon, Levy & Katzenstein, 2006). Many researchers have stumbled over attempts to identify what elements in psychotherapy lead to benefit. Studies done by our group (Waldron, Scharf, Hurst et al. 2004; Waldron, Scharf, Crouse, et al., 2004) found that it is the quality of the interventions, as judged by other seasoned clinicians listening to recordings of the therapeutic work, that contributes to advancing the patient’s work in treatment and in turn, benefit, irrespective of the particular type of intervention. These findings were made possible by developing scales to assess the various activities of patient, analyst and the analytic pair, described further below. But first, we present a brief and inevitably incomplete review of findings by other authors that have advanced knowledge in the field, first in regard to efficacy, and then of processes of psychoanalysis and psychoanalytic psychotherapy.

Some outstanding previous research on outcomes of psychoanalyses

Results supporting the efficacy of psychodynamic and psychoanalytic treatment are extensive (De Maat et al., 2013, 2006; Huber 2017; Knekt et al., 2013; Kivlighan, Wampold, 2015; Klug et al., 2016; Leichsenring, 2005; Leichensring & Leibing, 2007; Leuzinger-Bohleber, & Target, 2002; Sandell et al., 2000; Shedler, 2010; Waldron et al. 2017; Werbart, Forsström, Jeanneau, 2012; Wilczek et al., 2004), And yet more research is needed to clarify what aspects of psychoanalytic or psychodynamic work lead to greater benefit than other techniques.

Results about the degree to which a favorable outcome by the end of treatment contributes to the subsequent course of life (Falkenström et al., 2007; Huber 2017; Kantrowitz et al., 1987a, 1990a, b, c; Sandell et al., 2002) are much less extensive.

In the previous chapter we saw solid evidence of benefit from two related forms of psychoanalytic therapy applied to patients functioning at a borderline level and to those suffering from panic disorder. The therapies presented were developed on the basis of the characteristics specific to the patients to be treated. This is consistent with a long line of research demonstrating that therapies conceived for the specific problems of a patient are more effective than therapies delivered on a “one-size-fits-all” basis (Lambert, 2013). It is also consistent with research demonstrating that the diagnostic picture can help clinicians predict the best possible treatment procedures (Bram & Peebles, 2014; Lingiardi & McWilliams, 2017; Silberschatz, 2017).

Relating the processes of psychoanalyses to outcomes

The studies described, in addition to supporting the general efficacy of psychoanalysis, have also brought into question some previous therapeutic principles that had been taken for granted, without adequate empirical investigation.

The first hypothesis not supported by subsequent empirical research was that psychoanalysis helped patients to definitively abolish their core conflicts. The studies of Pfeffer et al., (1959, 1961, 1963), later replicated in San Francisco (Norman, Blacker, Oremland, & Barrett, 1976; Oremland, Blacker, & Norman, 1975) and Chicago (Schlessinger & Robbins, 1974; 1975) showed that neurotic conflicts are not “erased” in analysis, but they lose part of their strength, even if they can still give rise to symptoms and troublesome relational patterns. It turns out that in favorable cases the patient learns how to better deal with them via self-analysis, thanks to understanding aided via identification with the analyzing function of the analyst, and develops other coping skills that were previously not so visible, leading in turn to more favorable life circumstances and relationships.

The original descriptions of development of a psychoanalytic process was that the patient regresses in the analytic setting, then the analyst interprets the oedipal and pre-oedipal conflicts that derived from this regression and manifest themselves in the relationship with the analyst, leading to working through of the core conflicts. However, that description turns out not to fit most good outcomes of analysis. Frequently patients benefit from a psychoanalysis without a classically conceived analytic process taking place (Bachrach, Weber, Solomon, 1985; Wallerstein, 1986; Weber, Solomon, & Bachrach, 1985; Weber, Bachrach, & Solomon, 1985a, b).

Research also supports a related finding: expressive and supportive interventions are generally intertwined in all psychoanalyses and psychoanalytic psychotherapies, and supportive techniques can induce psychic changes as deep and stable as the changes obtained through expressive interventions (Wallerstein, 1986). Additionally, some research studies (e.g. Blatt, 1992) suggest that patients with different personalities (more anaclitic vs. more introjective) may benefit more from different approaches (more centered on the patient-therapist relationships for the anaclitic patient vs more insight oriented for the introjective).

The therapeutic alliance (Horvath, 2000; Rudolf, 1991; Rudolf & Mantz, 1993), has also been described as a good personal match between patient and therapist (Kantrowitz, 1986; 1987a, b,; 1990a, b, c; Leuzinger-Bohleber & Target, 2002) and a good relationship between patient and therapist (Freedman, 2002). However described, these components are potent therapeutic factors both in psychoanalysis and in psychotherapy in general. A conclusion is suggested: attention by the therapist to the therapeutic alliance deserves to be considered as important as other aspects of the analytic work (Safran and Muran, 2000 and many subsequent writings).

Transference interpretations have been shown in an unusual study to facilitate the forming of a therapeutic alliance early in psychoanalytic psychotherapy for those patients who have more disturbed relationships. The study involved matched comparisons in which each of 7 analytic therapists treated from 10 to 14 patients, who were randomly selected for treatment as usual, or to receive no transference interpretations in the first 100 sessions (Høglend et al. 2011).

There is evidence that a friendly, flexible, and open relational attitude, adjusted to the specific needs of each patient, is a key ingredient in psychoanalysis and in psychoanalytic psychotherapy (Curtis et al., 2004; Gabbard & Westen, 2003, Hamilton, 1996; Leuzinger-Bohleber & Target, 2002; Sandell et al., 2000; Weiss, 1993; Tessman, 2003 ), and it leads to more successful treatments than the benevolently neutral, detached and frustrating attitude previously recommended by theoreticians of American ego psychology (Gazzillo et al. 2017, Waldron et al. in preparation).

The data collected so far about the role of frequency of sessions and duration of the treatment suggest that greater frequency and longer duration have a synergic positive effect, with the greater frequency (at least two sessions per week) being more helpful for patients with acute problems, and greater duration (at least 140 weeks) for patients with chronic difficulties (Freedman, 2002; Sandell et al., 2000).

Empirically it has been difficult to determine early in psychoanalytic treatment if a patient will benefit from the continuing effort. An earlier study recommended waiting to determine potential benefit for a period of almost one year of analysis (Sashin, Eldred &Van Amerongen, 1975). Freud thought (1913) that it was necessary for a 6 months period of “trial analysis” in order to assess if a patient could benefit. However, efforts to predict benefit from early in treatment have not proved very successful (e.g. Horwitz, 1974). This area would benefit from more detailed exploration, particularly with the benefit of session recordings to evaluate more deeply the patient, therapist, and analytic pair’s functioning early in treatment[1].

Finally, some studies suggest that psychoanalysis could have better and longer lasting effects than other form of psychological treatment (Huber, Henrich, Clarkin, Klug, 2013; Sandell et al., 2000), but this is a result that needs more detailed exploration as well as replication, based upon many more recorded cases than heretofore. There has not been adequate funding so far for follow-up studies that extend for years, and yet the impact of psychoanalytic therapies on the rest of a person’s life is its greatest potential justification.

Introduction to our research on therapy processes and outcomes

As we explore in this chapter psychoanalytic (psychodynamic) therapy processes, we would like to articulate not just that the processes work, but how they work, and to know much more systematically what different successful psychoanalytic processes look like[2]. The research that will be the particular focus of the remainder of this chapter involves naturalistic observation of the processes of practicing senior psychoanalysts, using a variety of psychoanalytic approaches with the intent of helping patients achieve better psychological functioning. The present authors are interested in identifying those aspects of psychoanalytic techniques that are relevant to the deepening of the treatment and to the quality of the treatment outcome (Gazzillo et al., 2017, Waldron, Gazzillo, & Stukenberg, 2015).

Our study is of the largest collection of fully recorded psychoanalyses, numbering only 27 cases conducted by 7 psychoanalysts, in the collection of the Psychoanalytic Research Consortium, a not-for-profit organization whose purpose is to collect and make available to qualified researchers and teachers confidentialized samples from the collection (www.psychoanalyticresearch.org). A previous report details the substantial benefits occurring in the course of most of these analyses (Waldron et al. 2017).

Early efforts at evaluating psychoanalytic process tended to focus on cognitive aspects of the treatment, for example, what role did interpretation play, and what role did insight play in the patient’s changes. In order to assess such dimensions, many efforts were made to use clinical judgment to evaluate psychoanalytic sessions. But it turned out that systematic efforts to assess what was going on between patient and analyst showed that analyst-evaluators tended to have divergent views of cases they studied (e.g. Seitz, 1966). This divergence resulted in low reliability of measures and hence scant findings.

Coding Core Analytic Activities

Being aware of these problems, Waldron started a research group in 1985 to study recorded psychoanalyses in order to develop measures that improve reliability in psychoanalyst-researcher judgments about the processes of psychoanalysis. Our approach was to formulate clearly definitions of various psychoanalytic processes, and to develop a coding manual that would provide descriptions of these processes at different levels, using a 5-point Likert scale, rated from zero to four, with examples at the zero-point, two-point and four-point levels of the aspect being evaluated. We named our research group the Analytic Process Scales or APS Group, and spent several years rating recorded clinical material, which was divided into relevant segments, on the various patient and therapist scales, while continually refining our definitions and case illustrations[3]. Indeed, it turned out that we could rate reliably the presence and strength of what we call core analytic activities, including clarifying, interpreting, addressing transference, defenses and conflicts. We also assessed the analyst’s addressing issues from the developmental years of the patient, the patient’s self-esteem problems, and the overall quality of each analyst communication (which might be extended over several turns of speech).

At first, we replicated the earlier findings of unreliability: when raters only studied one session, each brought their own prejudices to bear, and so findings were unreliable from one rater to the next. But when the raters familiarized themselves more with the cases by studying some sessions from just prior to the material to be rated, their ratings converged, as long as they regularly referred to the descriptions given in the coding manual, to minimize rater drift (Waldron, Scharf, Hurst et al. 2004)![4]

What were the results of these evaluations? In a 2004 paper, we described: “[skillful psychoanalytic technique presumably involves knowing what to say, and when and how to say it. Does skillful technique have a positive impact upon the patient? The study described in this article relied on ratings by experienced psychoanalysts using the Analytic Process Scales (APS), a research instrument for assessing recorded psychoanalyses, in order to examine analytic interventions and patient productivity (greater understanding, affective engagement in the analytic process, and so on). In the three analytic cases studied, the authors found significant correlations between core analytic activities (e.g., interpretation of defenses, transference, and conflicts) and patient productivity immediately following the intervention, but only if it had been skillfully carried out.” (Waldron, Scharf, Crouse et al., 2004, p. 1079).

Thus we were able to establish that core analytic activities in a given segment enhanced the patient’s productivity in the next segment of the same session. Such enhanced productivity included a variety of ways of greater participation, conveying experiences both within the analytic setting and in the rest of life, increased self-reflection, and making meaningful connections between past and present. The question remained: did such apparent “mini” improvements indicate ongoing psychoanalytic process leading to greater improvement in quality of life?

Addressing the question of outcome meant that our research group stumbled over what then turned out to be our next major problem. We discovered that evaluation of outcomes left almost as much to be desired as that of processes. Self-evaluation by the patient is subject to the great disadvantage of both unreliability and bias (Shedler, Mayman & Manis 1993). Self-evaluations were nevertheless important and are widely used (for instance the Global Severity Index ratings from the SCL-90 and the derivative Brief Symptom Inventory (Derogatis and Savitz, 2000); the Beck Depression Inventory (Beck, Steer & Brown, 1996) and the Beck Anxiety Inventory (Beck, Epstein, Brown & Steer, 1988). Similarly, there are many clinician rated symptom scales, with the Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression (Hamilton, 1960) being a good early example.

But improvements in symptoms only captured a small part of what was important to patients (Connolly & Strupp, 1996). We became familiar with the Shedler Westen Assessment Procedure (SWAP; Shedler & Westen, 2007), referenced earlier in the chapter, a measure based upon 200 descriptive judgments by the therapist or by clinician-raters of recorded material. We then developed a Psychological Health Index (PHI; Waldron et al., 2011) based upon scores from a standard population, permitting us to evaluate outcomes in a more reliable, clinically meaningful way than such global measures as the Global Assessment of Functioning. The SWAP also benefits from the 24 items in the SWAP evaluating aspects of healthy functioning, to give a fuller picture of the person rated.

Dynamic Interaction Scales

We realized that our Analytic Process Scales did not explore sufficiently the interpersonal aspects of the treatments being evaluated, which our experienced clinician raters were responding to in listening as they read the transcripts of the confidentialized recorded sessions. So we attempted to explore components of the ratings of the quality of the analyst’s communications that had proved so predictive of the patient becoming more productive in the subsequent material of the sessions. These more interpersonal dimensions were expressed in a new instrument called the Dynamic Interaction Scales (Waldron et al. 2013). Therapist scales include the degree to which the therapist is straightforward, warmly responsive, responsive moment-to-moment to the patient’s feelings, conveys aspects of his subjective experience or subjective response to the patient’s communications, and how well the therapist is working with and helping the patient work with his/her typical troubling patterns of relating and feelings. Patient scales include the degree to which the patient flexibly shifts to and from experiencing and reflecting, the degree to which there is a flexible interplay on the part of the patient between conscious waking life and dreams in this session, and how well the patient is working with his/her typical troubling patterns of relating and feelings. Interaction scales include the degree to which the patient experiences the therapist as empathic, the degree to which the therapist’s contribution is leading to the further development of the patient’s awareness of his or her own feelings, the degree to which there is an integration of understanding of the relationship with the therapist to other relationships, past or present, and the degree to which there is an emotionally meaningful engagement in the therapeutic relationship by the two parties. These variables were assessed for whole sessions with good reliability.

We describe these items of our scales here to highlight what we have found to be important: the need for a very detailed and specific assessment of the communications between the two parties in order to tap into the subtleties of the relationship, which in turn serves as the vehicle, so to say, for new experiences for the patient within the therapy or with significant others, leading to positive change.

Collaborative Research between the U.S. and Italy

Several years ago our New York group made a liaison with a group of psychoanalytic researchers at Sapienza University in Rome, Italy, under the leadership of Francesco Gazzillo, with the support of Vittorio Lingiardi. The Roman group proposed to study sessions from early, middle and late in the 27 fully audio recorded psychoanalyses in the PRC collection. They used the Analytic Process Scales and the Dynamic Interaction Scales to study the processes of 20 sessions from each of these treatments, and the SWAP and the GAF to study changes from early to late in the treatments (Waldron et al. 2013), in other words the outcomes of these analyses, at least as far as was evident toward the end of their treatments. Evidence derived from this study supported strongly that most of these treatments were substantially beneficial by the end of treatment.

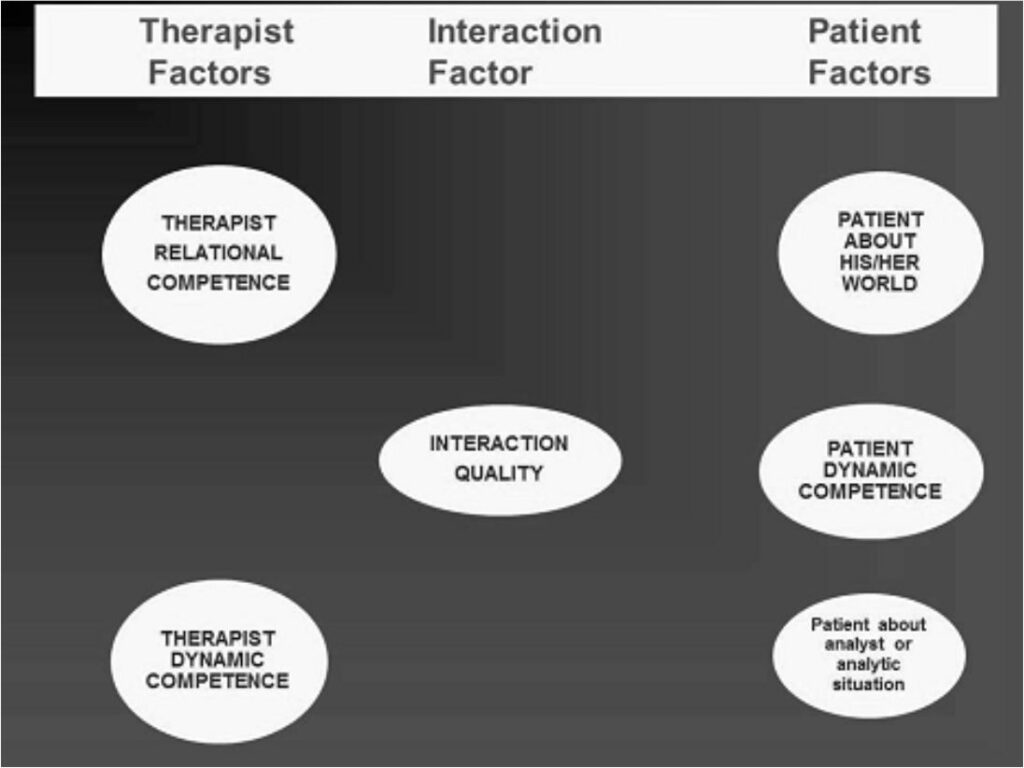

Our group has succeeded via factor analysis of the 540 rated sessions to identify six factors which emerge from the two psychodynamic process scales that we have developed and that characterize the analytic process we have observed in the 27 recorded analyses (Gazzillo et al. 2017). These factors include three patient factors (Patient Communication about the Analyst and the Analytic Situation, Patient Communication about their World, and Patient Dynamic Competence), two therapist factors (Therapist Dynamic Competence and Therapist Relational Competence) and an interaction factor (Interaction Quality). These three domains mirror the long established primary three domains that are related to treatment outcome: Patient, Alliance, and Therapist domains (in order of per cent of variance in outcome accounted for (Crits-Christoph, Gibbons, & Mukherjee, 2013)[5].

Results of Assessing the Interaction

The remainder of this section will demonstrate how it has been possible to develop more information than heretofore about the “how” of psychoanalytic work, i.e. the study of the contributions of the patient, the analyst, and the interaction between them by looking at the immediate impact of those factors. This we accomplish by measuring changes in the analytic process from one session to the next one in our sample, using sets of scales we and others have developed to measure presumably important aspects of psychoanalytic process. In contrast to the second order factor analysis referred to above, which linked the variables to the distal outcome of psychological health as determined by the SWAP, this analysis compares interventions with the psychological functioning of the patient in the subsequent session. Since we are interested in the immediate impact of the previous session, we studied only those sessions that were close together in time, mostly one to three days apart. There were 405 pairs of our 540 rated sessions which met this criterion.

As described above, we decided to explore what factors would adequately describe the 42 process variables we included in our analysis (Gazzillo et al., 2017). What emerged was the previously described set of analyst factors, patient factors and one interaction factor, perhaps best characterized by a graphic (Figure 1). The six ellipses contain the factors which emerged: on the left the therapist factors, on the right the patient factors, and in the middle the interaction factor.

Figure 1. The Six Factors for Therapist, Patient, and Interaction

Our study permitted us to make an examination, promised at the beginning of the chapter, of what kinds of analyst activity and relatedness led to apparent benefit for our 27 patients. First, we found that the average early score across the 27 patients for every one of the items in the APS and DIS scales which would be expected to have higher scores in cases proceeding well was higher in the eighteen patients who had substantial benefit from early to late in their analyses than the nine patients who showed little or no benefit. With such a small number of patients, the differences on any one item between the groups were not statistically significant, but the overall significance of 31 comparisons all coming up in one direction only is, of course, very high.[6]

There were 405 pairs of sessions that occurred within one day or a few days of each other. This provided us with the opportunity to test whether the higher scores on each of the six factors in one session impacted any of the other factors in the next session. In the following discussion we will call the antecedent session “session A”, and the subsequent session “session B”. We will also call a factor whose score in session A, when higher, was correlated with a higher score on a different factor in session B the causative factor, and the resultant session B factor the resultant factor[7]. Figure 2 shows which factors whose scores in session A correlated significantly with which other factors in session B. The starting point of each arrow is the score in session A, and the tip of the arrow is the score in session B.

Figure 2 The Presumed Causal Connections Among the Factors.

As shown in Figure 2, there are seven different ways that a given factor in Session A had a statistically significant impact on a factor in session B[8]. We will not focus here on each one of these, for reasons of space, but we will highlight the evidence that Therapist Relational Competence and Therapist Dynamic Competence in Session A impacted Interaction Quality in Session B, and also, Therapist Dynamic Competence and Interaction Quality in Session A predicted Patient Dynamic Competence in Session B. These factors are, arguably, those of most interest theoretically in that the two therapist factors reflect core psychodynamic items, the interaction quality reflects the raters’ evaluation of the therapeutic process, and the patient’s dynamic competence factor reflects aspects of patient functioning which many studies have linked to healthy psychological functioning. (Barber, Muran, McCarthy., & Keefe., 2013; )..In order to make these findings more meaningful to the reader, the following diagrams (Figures 3 through 7) list those items in each factor that were individually significantly contributing to the relationship found between Session A and Session B factor scores (adjusting for the Session A level of the resultant factor score)[9]. The relationship between each individual variable from a factor in Session A and the individual variables of the resultant factor in Session B were also calculated. Other individual items are also mentioned, which are part of the factor, but which did not attain the level of statistical significance in relation to items in the other factor.

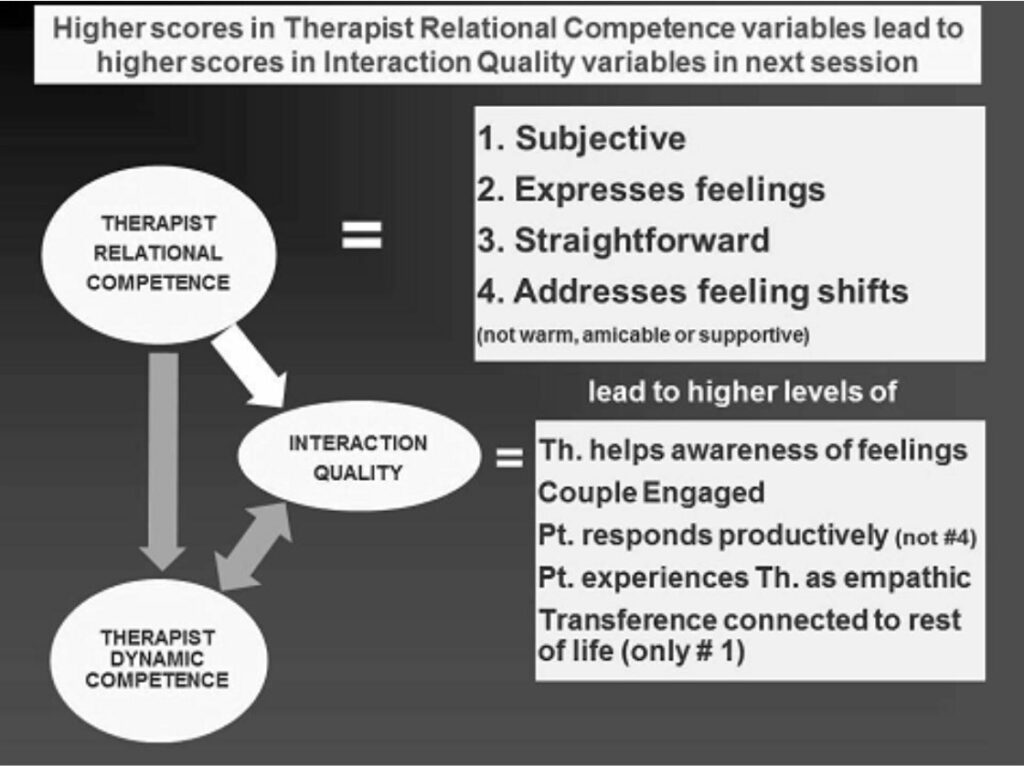

Figure 3 Therapist Relational Competence Improves Interaction Quality

When evaluating the impact of Therapist Relational Competence on Interaction Quality (Figure 3) we discovered that therapists who permit themselves to respond in a more subjective way, with more feeling, straightforwardly in session A appear to contribute to the interaction quality. In addition, therapists who address at a higher level moment-to-moment shifts in the patient’s feelings also appear to enhance significantly the subsequent interaction quality[10].

There are five items contributing to the Interaction Quality factor: Therapist helps patient to become more aware of his/her feelings; the therapeutic couple are engaged; the patient responds productively to the therapist’s communications; the patient experiences the therapist as empathic; and the patient’s reactions to the therapist or therapy situation are connected to the rest of his/her life. All four of the Therapist Relational Competence variables mentioned in the paragraph above appeared to impact each of the interaction quality variables, except for the variable called “the patient’s reactions to the therapist or the therapy situation are connected to the rest of his/her life”, which was only associated with the therapist responding in a subjective way to the patient in the previous session. Three Therapist Relational Competence variables were not significantly related to improved interaction quality – the therapist being warm, amicable, and supportive.

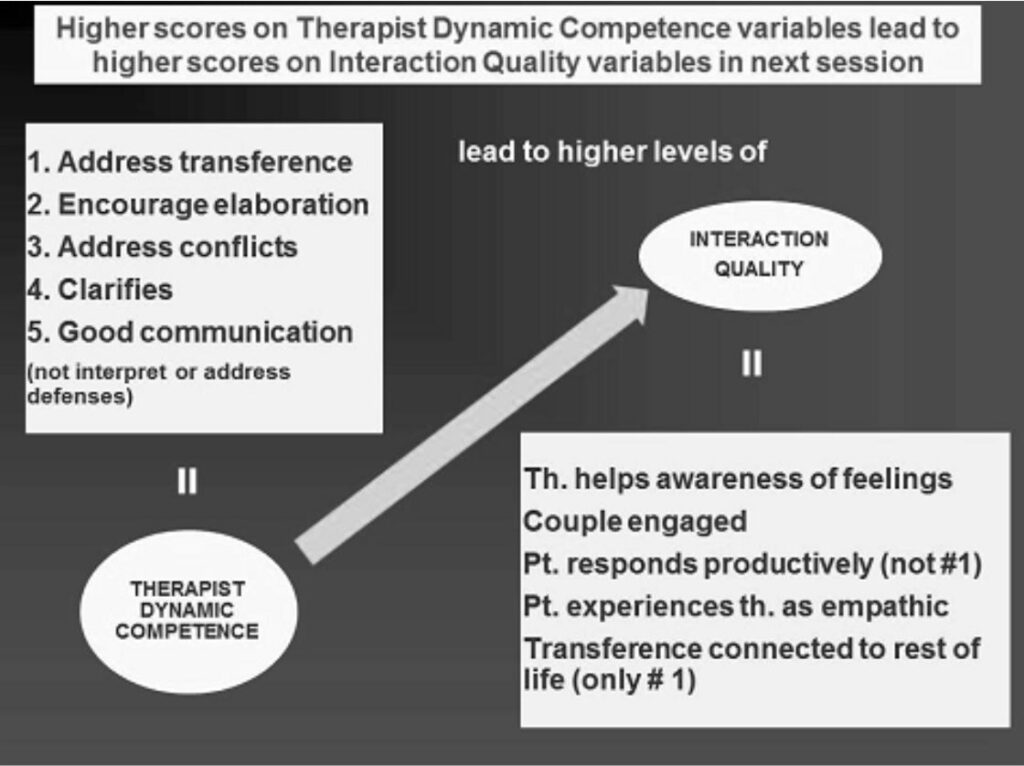

Figure 4 Therapist Dynamic Competence Increases Interaction Quality

Therapist Dynamic Competence (our second Therapist Factor) enhances Interaction quality (Fig. 4). Therapist dynamic competence is so named because the component items are central to psychodynamic theory about the active agents that a psychoanalyst or psychodynamic therapist employ with a patient. These include: addressing transference, encouraging elaboration, addressing conflicts, clarifying, and overall good communication all of which, when they were rated highly in session A contributed to higher interaction quality in session B. Two items were not significant predictors of improved interaction quality: interpretation and addressing defenses. It is also the case that addressing transference did not significantly relate to the interaction item connecting transference experiences to the rest of the patient’s life, but it was the only item that predicted that the patient would be rated as responding productively to the analyst.

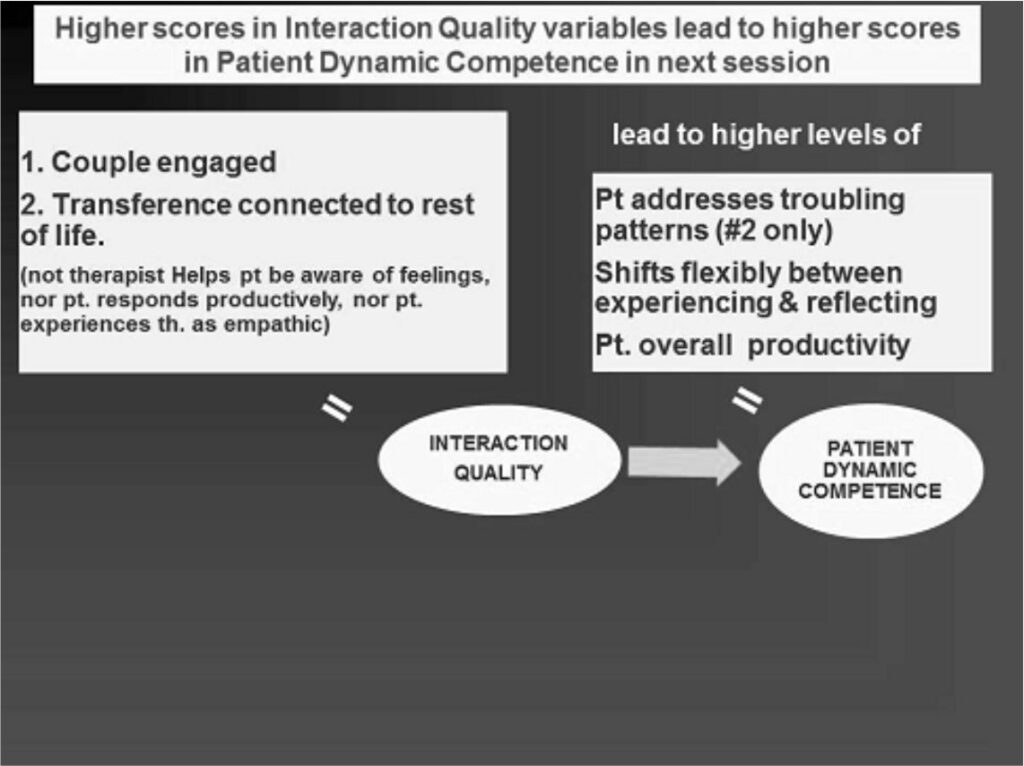

Figure 5 Interaction Quality Appears to Lead to Patient Dynamic Competence

The Patient Dynamic Competence Factor is the most important factor related to outcome we have found. It has six item loadings: oscillating flexibly between experiencing and reflecting; overall productivity; working on troublesome patterns of experiencing and relating to other people; maintaining self-reflection in a way that promotes self-understanding of their world; conveying experiences permitting the rater to understand their conflicts in their world; and communicating feelings that also contribute to rater’s understanding of their conflicts. All of these items would be expected to contribute to the patient’s overall competence in life, including the items which permit the therapist more effectively to aid the patient in what may be called internal competence in managing relations with the external world.

As we have discussed above, we see that Interaction Quality in Session A (which is influenced by therapist relational and dynamic competence) contributes to Patient Dynamic Competence in Session B, as we would expect. The two most significant items are the couple being engaged in the work/relationship and that connections are made between the patient’s reactions to the therapist or therapeutic situation and his/her life outside, past or present. This kind of process can be connected to the psychoanalytic concept of “working through” in the treatment.

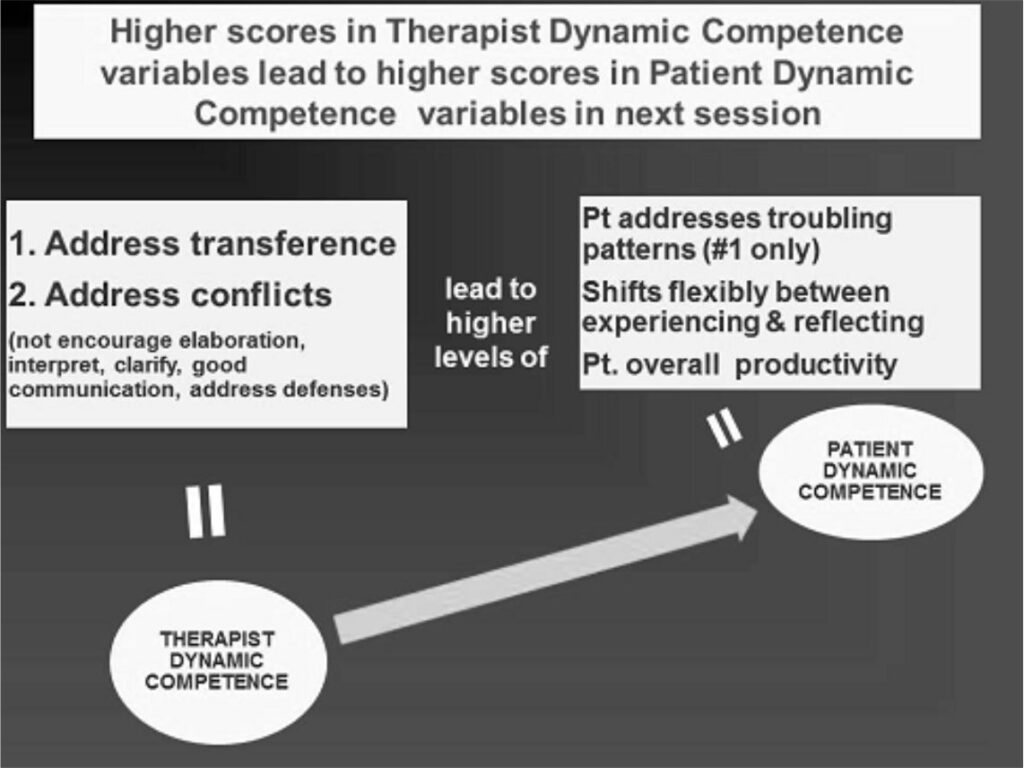

Figure 6 Therapist Dynamic Competence and Patient Dynamic Competence

Therapist Dynamic Competence in Session A – in addition to influencing Patient Dynamic Competence through contributing to patient Interaction Quality – also appears to directly enhance the Patient’s Dynamic Competence in Session B. Two key items in the Therapist Dynamic Competence variable specifically enhance the Patient Dynamic Competence in Session B: addressing transference and addressing conflicts. This finding directly supports central psychoanalytic therapeutic principles, for example as described in Charles Brenner’s (1973) classic Elementary Textbook of Psychoanalysis, building on Freud’s work and that of many others since.

Limitations

First, some of the modifications in therapeutic techniques and practices implied by these findings, based as they are on only 20 sessions per analysis, the work of 7 different analysts, and only 27 patients, may be desirable. On the other hand, since two-thirds of these analyses occurred several decades ago, and there have been modifications in technique widely adopted by practitioners, it might be erroneous and harmful to conclude that, in general among therapists, the more subjective the therapist, or the more warm, or the more the analyst promotes greater engagement with the patient, the better the treatment outcome! In other words, we cannot tell from these findings how broadly these findings may apply across a range of patients, or across a range of clinicians.

Secondly, we re-analyzed our data using multilevel structural equation modeling using Mplus (Muthén & Muthén, 2016) and lavaan (Rosseel, 2012) for taking into account the non-independence of the pairs of sessions. This approach changed the statistical significance of our results somewhat: while the overall patterning of relationships among the variables remained, the results did not consistently reach statistical significance when controlling for between-dyad effects. One central finding — therapist dynamic competence contributes to subsequent interaction quality — was confirmed as statistically significant using the more sophisticated procedures. This finding dovetails nicely with the important study by Høglend et al. (2011) mentioned earlier: transference interpretation led to a better relationship between patient and therapist. While a larger series of sessions from each case may well confirm the statistical significance of the other findings described in this chapter, it may turn out that some therapists/and or patients might show stronger or weaker relationships among the factors. Indeed, we will need to consider whether the between-group variance, itself, has clinical significance in that different subgroups of dyads show different patterning among the variables. These considerations epitomize the nature of psychoanalytic process research – as we deepen our exploration of patient-analyst interaction, our data comes closer to capturing the differing patterns of psychoanalytic processes for different patient-analyst pairs. We expect that this will lead to a more refined understanding of when and how psychoanalysis and long-term therapy works.

Implications and need for further research

Psychoanalysis and psychodynamic psychotherapy are processes that involve empathically connecting with the subjectivity of a patient and then finding ways to communicate through a variety of theoretically driven and empirically derived considerations, with the intent of helping the patient toward healthier functioning. Perhaps the most important immediate goal of the techniques is to help the patient more authentically experience their internal world – including aspects of which they have previously been unaware. Psychoanalytic process research intends to explore first the links of varying strengths between various aspects of what the therapist/analyst is doing, what the patient is doing, and how they are working together that lead to an increase in how deeply the patient engages in their internal life; secondly to explore whether and to what degree such a deeper engagement in the subjective experience of one’s life leads to an improvement in quality of life – reduction in symptoms, improved quality of relationships, and engagement in life.

When we look closely at analytic processes – seeing how the quality of the therapeutic engagement builds from session to session – we are able to demonstrate that the use of psychoanalytic techniques and the analyst’s attentiveness to the relationship impact the relationship between the patient and the analyst, and that this in turn impacts the engagement of the patient with their internal world. Further, the psychoanalytic technical skills of addressing transference and addressing conflict have a direct impact on the patient’s ability to immerse him- or herself in his or her internal world. When the patient is engaged in a high quality psychoanalytic interaction, the hoped for depth of subjective engagement is achieved. In future research we will use more sophisticated psychometric approaches that promise to capture the dynamic, reciprocal nature of relationships among our factors.

Some of our findings may be viewed as exploring the impact of the working alliance on the outcome of the treatment. Zilcha-Mano (2017) has clarified the trait versus the state aspect of working alliance. The work of the analyst in addressing the patient’s conflicts and transference reactions provides in favorable cases clear enhancement of the state aspect of the patient’s working alliance, thus facilitating the goals of therapy. The working alliance accounts for the second-most variance in treatment outcome after patient variables (Crits-Christoph, et al., 2013). In addition, Zilcha-Mano suggests that working on state alliance will increase the potential for trait alliance; that is, someone who has connected with a treater will be better able to connect with another treater or other persons of importance in their life in the future.

The research, then, supports not just that psychoanalysis works in the way that it is theorized to work, but it clarifies how various aspects of psychodynamic therapy work together to create the desired immediate and long term outcomes that are the raison d’être of psychoanalysis and psychodynamic psychotherapy. And it points the way to further research specifically to identify what may be missing in treatments that are not going well.

We need to address two issues in our ongoing and future research. First, we need to accumulate a much larger collection of recordings of psychoanalysis and psychotherapy than exists currently, and obtain the funding to accomplish the transformation of such recordings into confidentialized texts. We presently have discovered software for scanning all the sessions in our database of 27 psychoanalytic patients (close to 20,000 sessions), to convert the audio files into text, at a cost of around $1 per session. As a consequence, entire analyses could soon be searched readily for particular keywords. Then, only those sessions requiring specific study of the content could be confidentialized[11]. Various linguistic studies might show, for instance, that emotionally positive words increased in those cases that did well, and the points of such change, if there were such turning points, could then be studied in detail to highlight elements contributing to such changes.

The culture of psychoanalysts has been opposed to the intrusion of recordings so very few were made. But in today’s digital age patients are not opposed, even though psychoanalysts lag behind in willingness to undertake recording. The benefit from recording one’s work can be supported by study groups in which the members share the exploration of this highly complex activity and relationship. This educational experience can even be enhanced further if the treating analyst separately records his/her personal reactions and professional reflections in response to the sessions as the treatment continues, so that it would be possible to study these together with the recorded material to deepen the participants’ understandings.

The second great need is to study the impact of psychoanalyses upon the rest of people’s lives. We need to discover via systematic research how some psychoanalyses greatly enhance later quality of life, and be equally attentive to those cases that do not succeed. To do this adequately, we need to study as well the results of other therapeutic modalities, looking through the long lens of later life experience. As described earlier, there is evidence that psychoanalyses often have lasting effects not so readily seen as a result of other treatments, but the evidence is sparse, particularly in regard to a truly longitudinal perspective. We owe it to our patients to remedy this lack.

Over the next ten years, if we are able to increase the collection of recorded analyses and to study them closely, we will be able to ask more and more fine-grained questions about which kinds of communications at what points in an analysis help which patients achieve deeper engagement. And the potential exists for improving and refining our theories of therapeutic techniques based upon shared evidence — the very foundation of science. Until now, psychoanalytic teaching has mostly relied on detailed descriptions by analysts of their own work over time, and by study groups of clinicians discussing their work with colleagues. Such materials are described in articles and taught in seminars, but as we saw in the section above on “Relating processes of psychoanalyses to outcomes”, systematic examination of psychoanalytic theories of therapeutic action have not confirmed that all clinical psychoanalytic theories were supported by the evidence. We can expect that close study of many more recorded analyses, and comparing the processes of the analytic work with the outcomes both at the end of each treatment, and in post-analytic lives, should lead to many improvements in our theories of technique, in relation to the particularities of each individual patient, each individual analytic couple, and differences in the analysts themselves. As we help tease out the factors that contribute to better treatment outcomes, we hope that psychoanalytic and psychodynamic techniques will improve. This improvement will lead to increased attention to aspects of analytic processes in training and practice, and also to increased confidence in their importance as a result of further accumulated evidence.

There is yet another related reason for a focus on studying recorded psychoanalyses. All the members of our research group have experienced two important benefits from our ongoing work over thirty years. Studying the work of other analysts has enriched our sense of clinical possibilities, helped to further establish and consolidate our psychoanalytic identities as clinicians and researchers, and strengthened our sense of dedication to expanding psychoanalysis as a science through research on actual clinical work. Many writers have bemoaned the relative lack of support among psychoanalytic clinicians for research. If the collection and study of recorded analyses in study groups, first in the course of training and then with peers, becomes much more widespread, clinical support for an evolving psychoanalysis and psychoanalytic research within the profession would, we feel, be greatly enhanced. And the benefit from follow-up studies, with feedback, when permitted by the patient, would enhance our evolving skills as clinicians and teachers as well as supporting our dedication to this challenging and rewarding work.

References

Ablon, S. & Jones, E. E. (1998). How Expert Clinicians’ Prototypes of an Ideal Treatment Correlate with Outcome in Psychodynamic and Cognitive-behavioral Therapy. Psychotherapy Research, 8, 71-83.

Ablon, J. S., Levy, R. A., & Katzenstein, T. (2006). Beyond brand names of psychotherapy: Identifying empirically supported change processes. Psychotherapy, 4(2), 216-231. doi:10.1037/0033-3204.43.2.216.

Barber, J.P., Muran, J.C., McCarty, K.S., Keefe, J.R. (2013), Research on Dynamic Therapy. In Lambert, M. J. (Ed.). (2013). Bergin and Garfield’s Handbook of Psychotherapy and Behavior Change (6th ed.). New York, NY: John Wiley and Sons, Inc. ISBN: 978-4625-2202-

Beck, A. T., Epstein N., Brown G., & Steer R. A. (1988). An inventory for measuring clinical anxiety: Psychometric properties. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 56, 893–897. doi:10.1037/0022-006x.56.6.893

Beck, A. T., Steer R. A., & Brown, G. K. (1996). Manual for the Beck Depression Inventory-II. San Antonio, TX: Psychological Corporation.

Beutler, L. E., & Clarkin, J. F. (1990). Systematic Treatment Selection: Toward Targeted Therapeutic Interventions. NY, NY: Bruner/Mazel.

Blatt, S.J. (1992). The Differential Effect of Psychotherapy and Psychoanalysis with Anaclitic and Introjective Patients: The Menninger Psychotherapy Research Project Revisited. Journal of the American Psychoanalytic Association, 40, 691-724.

Bram, A., & Peebles, M.J. (2014). Psychological Testing That Matters. Washington DC: APA.

Brenner, C. (1973). An Elementary Textbook of Psychoanalysis. NY: Random House.

Crits-Christoph, P., Gibbons, M. B. C., & Mukherjee, D. (2013). Psychotherapy process-outome research. In M. J. Lambert (Eds.), Bergin and Garfield’s Handbook of Psychotherapy and Behavior Change 6th ed. (pp. 298 -340). New York: John Wiley and Sons, Inc. ISBN: 978-4625-2202-6

Connolly, M. B., & Strupp, H. H. (1996). Cluster Analysis of Patient Reported Psychotherapy Outcomes. Psychotherapy Research, 6, 30-42.

Curtis, R., Field, C., Knaan-Kostman, I. and Mannix, K. (2004). What 75 Psychoanalysts found helpful and hurtful in their own Analyses. Psychoanalytic Psychology, 21(2):183-202.

De Maat, S., de Jonghe, F., de Kraker, R., Leichsenring, F., Abbass, A., Luyten, P., Barber, J., Van, R., Dekker, J. (2013). The current state of the empirical evidence for psychoanalysis: A meta-analytic approach. Harvard Review of Psychiatry, 21: 107-137.

De Maat, S., Dekker, J., Schoevers, R., & De Jonghe, F. (2006). Relative efficacy of psychotherapy and pharmacotherapy in the treatment of depression: A meta-analysis. Psychotherapy Research, 16(5), 562-572. doi:10.1080/10503300600756402

Derogatis, L. R., Savitz, K. L. (2000). The SCL-90-R and the Brief Symptom Inventory (BSI) in Primary Care. In M. E. Maruish (Eds), Handbook of psychological assessment in primary care settings (pp. 297–334). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. ISBN 978-0-8058-2999-0. OCLC 42592750

Eagle, M.N. (2011), From Classical to Contemporary Psychoanalysis: A Critique and Integration. London: Routledge.

Falkenström, F., Grant, J., Broberg, J. and Sandell, R. (2007). Self-Analysis and Post-Termination Improvement after Psychoanalysis and Long-Term Psychotherapy. Journal of the American Psychoanalytic Association, 55: 629-674.

Fonagy, P. (2001). Attaccamento e funzione riflessiva (Attachment and reflective functioning). Milan (Italy): Raffaello Cortina.

Freedman, N. (2002). The research programme of the Institute for Psychoanalytic Training and Research (IPTAR). In M. Leuzinger-Bohleber, M. Target, M. Leuzinger-Bohleber, M. Target (Eds.), Outcomes of psychoanalytic treatment: Perspectives for therapists and researchers (pp. 264-279). Philadelphia, PA, US: Whurr Publishers.

Freud, S. (1900). The interpretation of dreams. In J. Strachey (Ed., Trans.), The standard edition of the complete works of Sigmund Freud (pp. 1–627). London, UK: Vintage.

Freud, S. (1913). On Beginning the Treatment (Further Recommendations on the Technique of Psycho-Analysis I). In S. Freud (Ed), The Standard Edition of the Complete Psychological Works of Sigmund Freud, Volume XII (1911-1913): The Case of Schreber, Papers on Technique and Other Works (pp. 121-144). London: Hogarth Press.

Freud, S. (1917). Mourning and Melancholia. In S. Freud (Ed), The Standard Edition of the Complete Psychological Works of Sigmund Freud, Volume XIV (1914-1916): On the History of the Psycho-Analytic Movement, Papers on Metapsychology and Other Works (pp. 237-258). London: Hogarth Press.

Gabbard, G. O., & Westen, D. (2003). Rethinking therapeutic action. International Journal of Psycho-Analysis, 84(4), 823-841.

Gazzillo, F., Lingiardi, V., Del Corno, F., Genova, F., Bornstein, R. F., Gordon, R. M., &McWilliams, N. (2015, April 13). Clinicians’ Emotional Responses and Psychodynamic Diagnostic Manual Adult Personality Disorders: A Clinically Relevant Empirical Investigation. Psychotherapy. Advance online publication. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/a0038799.

Gazzillo, F., Waldron, S., Gorman, B. S., Stukenberg, K., Genova, F., Ristucci, C., Faccini, F., & Mazza, C. (2017, July 27). The Components of Psychoanalysis: Factor Analyses of Process Measures of 27 Fully Recorded Psychoanalyses. Psychoanalytic Psychology. Advance online publication. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/pap0000155.

Gerber, A. J. (2012). Commentary: Neurobiology of Psychotherapy – State of the Art and Future Directions. In R. A. Levy, J. S. Ablon, & H. Kachele (Eds.), Psychodynamic Psychotherapy Research: Evidence-Based Practice and Practice-Based Evidence (pp. 187-192). NY: Springer Science+Business Media LLC. doi: 10.1007/978-1-60761-792-1_10.

Gullestad, F. S., Johansen, M.S., Hoglend, P, Karterud, S., Wilberg, T. (2013). Mentalization as a moderator of treatment effects: Findings from a randomized clinical trial for personality disorders. Psychotherapy Research, 23: 674-689.

Hamilton, M. (1960). A rating scale for depression. Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery and Psychiatry, 23, 56-62. doi:10.1136/jnnp.23.1.56 PMID 14399272

Hamilton, V. (1996). The Analyst’s Preconscious. Hillsdale, NJ: Analytic Press.

Horvath, A. O. (2000). The therapeutic relationship: From transference to alliance. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 56, 163-173.

Horwitz, L. (1974). Clinical Prediction in Psychotherapy. New York: Jason Aronson.

Høglend, P. Hersoug, A.G., Bøgwald, K.P., Amlo, S., Marble, A., Sørbye, Ø, Røssberg, J .I, O/ Ulberg, R., Gabbard, G. & Crits-Christoph, P. (2011). Effects of Transference Work in the Context of Therapeutic Alliance and Quality of Object Relations. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 79, 697–706.

Huber, D., Henrich, G., Clarkin, J., & Klug, G. (2013). Psychoanalytic Versus Psychodynamic Therapy for Depression: A Three-Year Follow-Up Study. Psychiatry: Interpersonal & Biological Processes, 76(2), 132-149.

Huber, D. (2017). Research evidence and the provision of long-term and open-ended psychotherapy and counselling in Germany. European Journal of Psychotherapy and Counselling, 19(2), 158-174.

Kantrowitz, J. L. (1986). The Role of the Patient-Analyst “Match” in the Outcome of Psychoanalysis. Annals of Psychoanalysis, 14, 273-297.

Kantrowitz, J. L., Katz, A. L., Paolitto F., Sashin, J., & Solomon, L. (1987a). Changes in the level and quality of object relations in psychoanalysis: Follow-up of a longitudinal prospective study. Journal of the American Psychoanalytic Association, 35, 23-46.

Kantrowitz, J. L., Katz, A. L., Paolitto F., Sashin, J., & Solomon, L. (1987b). The role of reality testing in psychoanalysis: Follow-up of 22 cases. Journal of the American Psychoanalytic Association, 35, 367-385.

Kivlighan, D., Goldberg, S. B., Abbas, M., Pace, B. T., Yulish, N. E., Thomas, J. G., &

Wampold, B. E. (2015). The enduring effects of psychodynamic treatments vis-à-vis

alternative treatments: A multilevel longitudinal meta-analysis. Clinical Psychology Review, 401-14. doi:10.1016/j.cpr.2015.05.003

Klug, G., Zimmerman, J., & Huber, D. (2016). Outcome trajectories and mediation in psychotherapeutic treatments of major depression. Journal of the American Psychoanalytic Association, 64(2), 307-343.

Knekt, P., Lindfors, O., Sares-Jaske, L., Virtala, E., & Harkanen, T. (2013). Randomized trial on the effectiveness of long- and short-term psychotherapy on psychiatric symptoms and working ability during a 5-year follow-up. Nordic Journal of Psychiatry, 67(1), 59-68.

Lambert, M. J. (Ed.). (2013). Bergin and Garfield’s Handbook of Psychotherapy and Behavior Change (6th ed.). New York, NY: John Wiley and Sons, Inc. ISBN: 978-4625-2202-

Leichsenring, F., & Leibing, E. (2007). Psychodynamic psychotherapy: A systematic review of techniques, indications and empirical evidence. Psychology and Psychotherapy: Theory, Research, and Practice, 80, 217-228. doi:10.1348/147608306X117394

Leuzinger-Bohleber, M. & Target, M. (Eds.). (2002). The Outcomes of Psychoanalytic Treatment. London: Whurr Books.

Lingiardi, V., & McWilliams, N. (Eds.). (2017). Psychodynamic Diagnostic Manual: 2nd Edition. NY: Guilford Press.

Luborsky, L., Singer, B., & Luborsky, L. (1975). Is it true that ‘everyone has won and all must have prizes”? Archives of General Psychiatry, 32, 995–1008, doi:10.1001/archpsyc.1975.01760260059004.

Muthén, L. K., & Muthén, B. O. (2016). Mplus User’s Guide: Statistical Analysis with Latent Variables: User’s Guide (Version 8). Muthén & Muthén.

Norcross, John C. Ed. (2011). Psychotherapy Relationships That Work: Evidence – Based Responsiveness. New York, Oxford University Press.

Oberski, D. L. (2014). lavaan. survey: An R package for complex survey analysis of structural equation models. Journal of Statistical Software, 57(1), 1-27.

Oremland, J. D., Blacker, K. H., & Norman, H. F. (1975). Incompleteness in “Successful” psychoanalyses: A follow-up study. Journal of the American Psychoanalytic Association, 23, 819-844.

R Core Team (2016). R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria. URL https://www.R-project.org/.

Rosseel, Y (2012). lavaan: An R Package for Structural Equation Modeling. Journal of Statistical Software, 48(2), 1-36. URL http://www.jstatsoft.org/v48/i02/.

Rosenzweig, S. (1936). Some implicit common factors in diverse methods of psychotherapy. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 6(3), 412–15. doi:10.1111/j.1939-0025.1936.tb05248.

Rudolf, G. (1991). Free University of Berlin, Berlin Psychotherapy Study. In L. Beutler, M. Crago (Eds), Psychotherapy Research. An International Review of Programmatic Studies. Washington: American Psychological Association.

Rudolf, G., & Manz, R. (1993). Zur prognostischen Bedentung der therapeutischen Arbeitsbeziehung aus der Perspektive von Patienten und Therapeuten. Psychotherapie, Pychosomatik und Medizinsiche Psychologie, 43, 193-199.

Safran, J., & Muran, J. C. (2000). Negotiating the Therapeutic Alliance, a Relational Treatment Guide. New York: Guilford Press.

Schachter, J., & Kächele, H. (2012). Arbitrariness, Psychoanalytic Identity and Psychoanalytic Research. Romanian Journal of Psychoanalysis/Revue Roumain de Psychanalyse, 5(2), 137-161.

Shore, A.N. (1994), Affect Regulation and the Origin of the Self: The Neurobiology of Emotional Development. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Seitz, P. F. D. (1966). The consensus problem in psychoanalytic research. In L. A. Gottschalk, A. H. Auerbach (Eds.), Methods of research in psychotherapy (pp. 209-225). New York: Appleton-Century-Crofts.

Shedler, J. (2010). The efficacy of psychodynamic psychotherapy. American Journal of Psychology, 65, 98-109. doi: 10.1037/a0018378

Shedler J., Mayman, M., & Manis, M. (1993). The illusion of mental health. The American Psychologist, 48(11), 1117-1131.

Shedler, J., & Westen, D. (2007). The Shedler-Westen Assessment Procedure (SWAP): Making personality diagnosis clinically meaningful. Journal of Personality Assessment, 89, 41-55.

Shore, A.N. (1994), Affect Regulation and the Origin of the Self: The Neurobiology of Emotional Development. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Silberschatz, G. (2017). Improving the yield of psychotherapy research. Psychotherapy Research, 27:1, 1-13, DOI: 10.1080/10503307.2015.1076202

Sloane, R. B., Staples, F. R., Cristol, A. H., Yorkson, N. J., & Whipple, K. (1975). Psychotherapy Versus Behavior Therapy. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Solms, M. (2017). The scientific standing of psychoanalysis. British Journal of Psychiatry – International. In press.

Stern, D.N. (1985). The interpersonal world of the infant: a view from psychaoanlysis and developmental psychology. London: Karnack

Tessman, L. (2003). The Analyst’s Analyst Within. Hillsdale, NJ: Analytic Press.

Waldron, S., Gazzillo, F., Genova, F., & Lingiardi, V. (2013). Relational and classical elements in psychoanalyses: an empirical study with case illustrations. Psychoanalytic Psychology, 30, 4, 567-600. DOI: 10.1037/a0033959. ISNN: 0736-9735.

Waldron, S., Gazzillo, F., Stukenberg, K. & Gorman, B. (2017). What leads to Benefit in Recorded Psychoanalyses? In Preparation.

Waldron, S., Gazzillo, F., & Stukenberg, K. (2015). Do the Processes of Psychoanalytic Work Lead to Benefit? Studies by the APS Research Group and the Psychoanalytic Research Consortium, Psychoanalytic Inquiry, 35(1), 169-184, doi: 10.1080/07351690.2015.987602

Waldron, S., Gordon, R. M., Gazzillo, F. (2017). Assessment within the PDM-2 Framework. In V. Lingiardi, N. McWilliams (Eds), Psychodynamic Diagnostic Manual Second Edition (pp. 889-972). New York: The Guilford Press.

Waldron, S., & Helm, F. (2004). Psychodynamic features of two cognitive behavioural and one psychodynamic treatment compared using the Analytic Process Scales. Canadian Journal of Psychoanalysis, 12, 346-368.

Waldron, S., Moscovitz, S., Lundin, J., Helm, F., Jemerin, J., & Gorman, B. (2011). Evaluating the Outcomes of Psychotherapies: The Personality Health Index. Psychoanalytic Psychology, 28, 363-388.

Waldron, S., Scharf, R. D., Crouse, J., Firestein, S. K. Burton, A., & Hurst, D. (2004). Saying the right thing at the right time: a view through the lens of the Analytic Process Scales (APS). Psychoanalytic Quarterly, 73, 1079-1125.

Waldron, S., Scharf, R. D., Hurst, D., Firestein, S. K., & Burton, A. (2004). What happens in a psychoanalysis?. The International Journal of Psychoanalysis, 85(2), 443-466.

Wallerstein, R. S. (1986), Forty-two Lives in Treatment: A study of Psychoanalysis and Psychotherapy. Guilford, New York.

Wampold, B. E., & Imel, Z. E. (2015). The great psychotherapy debate: The evidence for what makes psychotherapy work. Second Edition. New York: Routledge. ISBN: 978-0-8058-5709-2

Weber, J. J., Bachrach, H. M., & Solomon, M. (1985a). Factors Associated with the Outcome of Psychoanalysis: Report of the Columbia Psychoanalytic Center Research Project (II). International Review of Psycho-Analysis, 12, 127-141.

Weber, J. J., Bachrach, H.M., & Solomon, M. (1985b). Factors Associated with the Outcome of Psychoanalysis: Report of the Columbia Psychoanalytic Center Research Project (III). International Review of Psycho-Analysis, 12, 251-262.

Weber, J. J., Solomon, M., & Bachrach, H.M. (1985). Characteristics of Psychoanalytic Clinic Patients: Report of the Columbia Psychoanalytic Center Research Project (I). International Review of Psycho-Analysis, 12, 13-24.

Weiss, J. (1993). Empirical Studies of the Psychoanalytic Process. Journal of the American Psychoanalytic Association, 41S(Supplement), 7-29.

Werbart, A., Forsstrom, D, & Jeanneau, M. (2012). Long-term outcomes of psychodynamic residential treatment for severely disturbed young adults: A naturalistic study at a Swedish therapeutic community. Nordic Journal of Psychiatry 66(6), 367-375.

Westen, D., Novotny, C. M., & Thompson-Brenner, H. (2004). The empirical status of empirically supported psychotherapies: Assumptions, findings, and reporting in controlled clinical trials. Psychological Bulletin, 130, 631-663.

Wilczek, A., Barber, J. P., Gustavsson, J. P., Åsberg, M. and Weinryb, R. M. (2004). Change after Long-Term Psychoanalytic Psychotherapy. Journal of the American Psychoanalytic Association, 52: 1163-1184

Zilcha-Mano, S. (2017). Is the alliance really therapeutic? Revisiting this question in light of recent methodological advances. American Psychologist, 72(4), 311-325.

_________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

[1] One of the authors’ research group is currently exploring this possibility via studying in great detail early sessions of 27 recorded analyses.

[2] For a review of other measures useful for characterizing psychoanalyses, such as the Psychotherapy Process Q-Set and the Comprehensive Psychotherapy Process Scales, see Lingiardi & McWilliams, 2017, pp. 889-972

[3] Our research group includes or has included Fonya Helm, Seymour Moscovitz, Karl Stukenberg, Robert Scharf, Marianne Goldberger, Stephen Firestein, Anna Burton, John Lundin, and John Jemerin.

[4] The 81-page APS Coding Manual is available from the first author (woodywald@earthlink.net).

[5] Because therapist factors account for less variance in the outcome of a treatment, we have limited ability to impact the outcome of a treatment. The wise treater chooses her or his patients carefully and then works carefully to have a good relationship with them! That said, because the therapist variables are the part of the equation that we have the most control over, we as a field have devoted a great deal of our research efforts to these variables (see Lambert, 2013 for various reviews of the research on these variables) and our group continues in this tradition.

[6] The likelihood of a coin coming up “heads” 31 times in a row by chance is less than one in 2 million. Since each variable is not fully independent of the others (the same group of raters is evaluating each of the 540 sessions), this estimate of probability may only be used to indicate significance in a very approximate way.

[7] In making these calculations, partial correlations were used, holding the level of the resultant factor in session A constant, to eliminate any effect of its previous level on its level in session B. Full details of this study, of the additional statistical procedures applied, and detailed descriptions of the items contributing to each factor will be available by emailing Waldron at woodywald@earthlink.net.

[8] We used partial correlations to control for the previous level of the Session B factor level, to highlight the particular relationship between Session A level of a given factor (and later also of the component variables of the factor) and a change in the level of the Session B factor. However, this method must be considered as approximate and preliminary, because the 405 pairs of sessions are not fully independent of one another. They are clustered first because each group of 20 sessions is from a unique patient, and there is clustering by therapist as well, since there are only seven therapists. We have chosen for this publication to keep the partial correlations because partial correlations are easier for clinicians to grasp. We have performed more sophisticated analyses using the lavaan (Rosseel, 2012).and lavaan.survey (Oberski, 2014). procedures in the R statistical programs both uncorrected and corrected for clustering of observations within patient and therapist in the R statistical package (R core team, 2016) We discuss further below the significance of the incomplete patterns of support from these procedures for the partial correlations as reported here.

[9] The significance of each partial correlation between variables constituting a presumed causative factor and variables in the dependent factor is again subject to the limitation of the partial non-independence of scores in the 405 sessions (clustered by patient and therapist), as well as by the sheer number of partial correlations calculated. However, the majority of all the calculations were significant at least at the .05 level, so we may feel moderate confidence in the findings.

[10] The reader should note that items from a given factor which are printed in small type, preceded by the word “not”, are simply items that did not reach the level of clinical significance, even though they almost invariably showed correlations in the expected direction. In this example the text reads “not warm, amicable, or supportive.”

[11] Of course the confidentializing of each session after conversion would still cost approximately $20 per session, plus another $50 per session to produce confidentialized audio files for listening, if that were desirable.